As India celebrates its 79th year of independence, this article explores the deeper truths behind August 15—from the symbolic meaning of the national flag to the overlooked voices in the freedom struggle. It also highlights how many communities, including Dalits, religious minorities, and women, still fight for equality today. A curated reading list for children and teens offers a way forward through inclusive education.

Every year on August 15, India erupts into celebration—flags flutter from balconies, schoolchildren sing patriotic songs, and the Prime Minister addresses the nation from the Red Fort. But behind the colourful displays and ceremonial speeches lies a much deeper story—a story of resistance and resilience, but also of rupture and ongoing reckoning.

The Indian tricolour, which often takes centre stage on this day, tells a quiet story of its own. Saffron stands for courage and sacrifice, white for truth and peace, and green for prosperity. At its heart lies the Ashoka Chakra, a deep navy wheel that represents dharma, justice, and motion. Its origins trace back to Emperor Ashoka, who reigned during the 3rd century BCE. After waging the brutal Kalinga War around 261 BCE, he turned away from violence and embraced Buddhist principles (Thapar, 1997). His journey from conquest to compassion reminds us that true strength lies not in domination, but in transformation.

India’s independence, won in 1947, was not handed down from a single podium nor secured by one voice. It was forged in the fires of collective resistance—from the satyagrahas of Mohandas K. Gandhi—mass campaigns of “truth-force” that used peaceful protest to confront injustice—to the strategy of non-violent civil disobedience, where ordinary citizens deliberately broke unjust colonial laws without resorting to violence. These movements mobilised millions, inspiring hope across the country. Bhagat Singh’s fiery declarations and ultimate martyrdom became a rallying cry for revolution.

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, representing the Dalit community, not only drafted the Constitution but also fought tirelessly to dismantle caste oppression through legal reform. Subhas Chandra Bose raised the Indian National Army to fight the British militarily, rallying support across Southeast Asia.

Women like Aruna Asaf Ali, who famously hoisted the flag during the Quit India Movement—a nationwide 1942 campaign demanding an immediate end to British rule—Sarojini Naidu, the “Nightingale of India” whose oratory inspired crowds, and Begum Rokeya, who championed education for Muslim girls in Bengal, defied both patriarchy and colonialism.

From Punjab, Sikh leader Udham Singh avenged the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, symbolising a demand for justice that crossed communal lines. Parsi industrialist Dadabhai Naoroji, the “Grand Old Man of India,” laid the intellectual foundations of economic nationalism through his drain theory, exposing how British policies impoverished India. Tribal leader Birsa Munda led uprisings in the late 19th century against both colonial and feudal exploitation, leaving a lasting legacy for Adivasi rights. Christian freedom fighter Annie Besant not only campaigned for India’s self-rule but also served as the first woman president of the Indian National Congress.

From the Northeast, Rani Gaidinliu of Nagaland mobilised her community against British rule from the 1930s, combining spiritual leadership with armed resistance, and was later honoured as the “Daughter of the Hills.” Kanaklata Barua of Assam, just 17 years old, was martyred while leading a procession to hoist the national flag during the Quit India Movement, becoming a symbol of youthful courage.

Leaders within the Muslim League, like Muhammad Ali Jinnah, played decisive roles in shaping parallel but pivotal paths. Jinnah envisioned a separate homeland for Muslims, arguing that their political and cultural rights would be insecure in a Hindu-majority India. The name Pakistan came from a 1933 proposal by Choudhry Rahmat Ali, combining Pak (meaning “pure” in Persian/Urdu) with -stan (meaning “land”), and also as an acronym representing the regions Punjab, Afghania (North-West Frontier Province), Kashmir, Sindh, and Baluchistan. Maulana Azad, on the other hand, worked within a united India vision, and as the first Education Minister, laid the foundations for India’s modern schooling system.

The freedom movement, in truth, was a tapestry of intersecting identities and ideologies—Hindu, Muslim, Dalit, Sikh, Christian, Parsi, tribal, Northeast, men and women, radicals and reformers—all contributing in ways history has often tried to simplify or erase.

But freedom came with a devastating cost.

The Partition of 1947 split the subcontinent into India and Pakistan, unleashing one of the largest and bloodiest migrations in human history. More than 15 million people were displaced; over a million were killed. Families were uprooted overnight, trains turned into moving graveyards, and neighbours became strangers across hastily drawn borders (Talbot & Singh, 2009). The scars of Partition didn’t just shape national boundaries—they fractured communities and embedded mistrusts that persist to this day.

British colonisers left behind not just railways and bureaucracy, but a deeply embedded policy of “divide and rule.” This legacy continues to echo in modern India through religious polarisation, caste-based violence, and institutional inequality (Ambedkar, 2002). While we may have ended colonial rule, we are still grappling with the divisions it deepened.

So, what does it mean to be free in India today?

For young people growing up in a digital, fast-paced world, patriotism often looks like a hashtag, a reel, or a repost. But real freedom lies in understanding what we’ve inherited—and choosing how we carry it forward. It lies in questioning narratives that exclude. In reading the stories of those pushed to the margins. In speaking up in classrooms, in WhatsApp groups, and on the streets when injustice shows its face.

Because freedom was never meant to be static. It is not something that was won once and remains forever. It must be renewed constantly—by questioning, by dissenting, by dreaming boldly.

And yet, many are still waiting to taste it.

Dalit communities—historically referred to as “untouchables” under the Hindu caste system—were placed outside the four-fold varna hierarchy (Brahmin – priests, Kshatriya – warriors, Vaishya – traders, Shudra – labourers). Denied both social and spiritual equality, they were forced into the most stigmatised and dehumanising forms of labour, such as manual scavenging, disposing of animal carcasses, and cleaning streets. They were barred from temples, prevented from using common wells, and often made to live in segregated settlements.

During the freedom struggle, Mahatma Gandhi sought to address their plight, popularising the term “Harijan” (“children of God”) in place of the derogatory “untouchable.” While intended to uplift, many Dalit leaders—including Dr. B. R. Ambedkar—rejected the term, arguing that it was patronising and left the oppressive caste hierarchy intact. Gandhi’s reformist approach focused on moral persuasion rather than dismantling structural inequality.

Tensions between Gandhi and Ambedkar peaked in 1932 with the Poona Pact. The British had proposed separate electorates for Dalits to secure their political representation—an idea Ambedkar supported as essential for genuine empowerment. Gandhi, opposing what he saw as the fragmentation of Hindu society, went on a fast-unto-death. The compromise, the Poona Pact, granted reserved seats for Dalits but within joint electorates, making them politically dependent on dominant caste voters. While it increased seat numbers, many scholars argue it limited Dalit autonomy and had lasting consequences for their political voice.

Even today, discrimination persists despite constitutional safeguards championed by Ambedkar. Dalit children in some schools are still made to sit separately in midday meal lines or are assigned menial chores. In Uttarakhand’s Almora district, Dalit girls were reportedly barred from entering a temple during a festival (Times of India, 2023). In March 2025, a Dalit father in the same state withdrew his complaint after being denied temple entry for his daughter’s wedding, reportedly under social pressure (The Print, 2025). In Ahmedabad, a 28-year-old Dalit contractual worker died by suicide after alleging repeated caste-based harassment from a superior, including being forced to clean toilets (Times of India, 2025).

Ambedkar’s legacy remains deeply influential—millions venerate him as a crusader for social justice and the chief architect of the Constitution—yet he is often underrepresented in mainstream independence narratives compared to other leaders. His vision for India was not just political freedom, but the dismantling of centuries-old systems of inequality.

Religious minorities, too, are often reduced to headlines or made scapegoats in a tense political climate, as seen in communal riots or targeted misinformation campaigns. Women—especially from marginalised communities—still fight for safety, autonomy, and opportunity, with gender-based violence and wage inequality making national news far too often.

We may be free on paper. But for too many, that freedom hasn’t reached their doorstep.

This August 15th, as we remember the heroes of the past, let’s not forget the work that remains. Let’s move beyond hollow patriotism and into a more courageous form—one that acknowledges our unfinished revolutions.

Because independence was the beginning.

Interdependence—and justice for all—is the journey.

If freedom is to be meaningful, it must be understood, discussed, and passed on to the next generation—not just as a date in history, but as a living, evolving idea. Stories have the power to bridge that gap. By reading about independence, Partition, and social justice, children can see the struggles and victories of the past while connecting them to the issues of today. That is why I have curated a list of children’s books that speak to both the heart and the mind—books that invite young readers to question, empathise, and imagine a more just future.

📚 Reading Corner: Children’s Books on Indian Independence, Partition, and Social Justice

📗 Chachaji’s Cup by Uma Krishnaswami Fiction | Picture Book | Age 6+ Summary: Neel’s great-uncle treasures a teacup that carries memories of Partition. This quiet story helps children understand loss, migration, and memory through a family heirloom.

📗 My Gandhi Scrapbook by Sandhya Rao

Nonfiction | Biography (Illustrated) | Age 6+

Summary: A lively scrapbook-style biography of Mahatma Gandhi filled with photos, doodles, quotes, and facts. Engaging for kids who like visual, hands-on learning.

📗 The Secret Kingdom: Nek Chand… by Barb Rosenstock Nonfiction / Picture Book | Age 7+ Summary: Celebrates Nek Chand, who built Chandigarh’s famous Rock Garden using discarded materials after Partition. A story of resilience, art, and transforming trauma into beauty.

📗 India’s Freedom Story by Ira Saxena & Nilima Sinha Nonfiction / History Overview | Age 9–12 Summary: Engaging, timeline-based narrative of India’s road to independence. It connects major events with international movements, building context and inspiring civic pride.

📗 The Night Diary by Veera Hiranandani Fiction | Historical Fiction | Age 10–13 Summary: Nisha, a 12-year-old girl who is half-Hindu, half-Muslim, writes diary entries as her family flees during Partition. A sensitive, award-winning story of identity, fear, and hope.

📗 The Train to Tanjore by Devika Rangachari Fiction | Caste Awareness | Age 10–13 Summary: Follow Thambi as he travels through South India’s forests in 1942. The novel peels back layers of caste, colonialism, and youthful courage amid social change.

📗 A Flag, A Song and a Pinch of Salt by Subhadra Sen Gupta. Nonfiction | Short Biographies | Age 9–12 Summary: Stories of India’s lesser-known freedom fighters—tailor-made for young readers who want to go beyond Gandhi and Nehru. Perfect for school projects or curiosity-driven kids.

📗 The Line They Drew Through Us by Hiba Noor Khan Fiction | Partition & Friendship | Age 9+ Summary: Three friends—Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh—born on the same day face community violence after Partition. The novel explores friendship, identity, and healing.

📗 Amil and the After by Veera Hiranandani Fiction | Partition Aftermath | Age 10–13 Summary: Told in verse, this sequel to The Night Diary explores twin Amil’s grief and healing in the wake of Partition. A gentle look at trauma, art, and adaptation.

📗 The Partition Project by Saadia Faruqi Fiction | Cross-Generational Narrative | Age 10–14 Summary: Pakistani-American Mahnoor reconnects with her grandmother’s Partition experiences while working on a school documentary. Explores memory, identity, and diasporic heritage.

📗 Bhimayana: Experiences of Untouchability by Srividya Natarajan & S. Anand, Art by Durgabai & Subhash Vyam Graphic Nonfiction | Social Justice | Age 13+ Summary: This striking graphic novel uses Gond tribal art to tell the story of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar and his fight against caste discrimination. Visually rich and deeply moving.

📗 Ambedkar: India’s Crusader for Human Rights (Campfire Graphic Novels) by Kieron Moore; Art: Sachin Nagar Nonfiction | Graphic Biography| Age 12+ Summary: From a boy barred from the school water jug to the chief architect of India’s Constitution, Ambedkar’s journey is shown through vivid, sequential art. The book doesn’t shy away from caste oppression (Mahad Satyagraha, temple-entry struggles) and also highlights his scholarship, legal reforms, and Buddhist conversion—inviting readers to see civil rights as ongoing work rather than a finished chapter.

📗 Young Uncle Comes to Town by Vandana Singh Fiction | Humorous Slice of Life | Age 11–14 Summary: A whimsical, socially aware story about a quirky uncle whose actions gently challenge societal norms. A subtle introduction to alternative thinking.

📗 A Time to Burnish by Radhika Nathan Fiction | Caste, Politics | Age 14+ Summary: A lesser-known gem about a girl discovering her activist father’s role in caste resistance. Tackles memory, rebellion, and truth.

📗 No Guns at My Son’s Funeral by Paro Anand Fiction | Terrorism & Patriotism | Age 13–17 Summary: A gripping story set in Kashmir, exploring how young minds can be radicalised in the name of freedom. Raises questions about identity and nationalism.

📗 We the Children of India by Leila Seth, illustrated by Bindia Thapar Nonfiction | Constitution & Rights | Age 10–14 Summary: A colourful, child-friendly explanation of the Indian Constitution’s Preamble. Teaches kids how freedom connects to justice and rights.

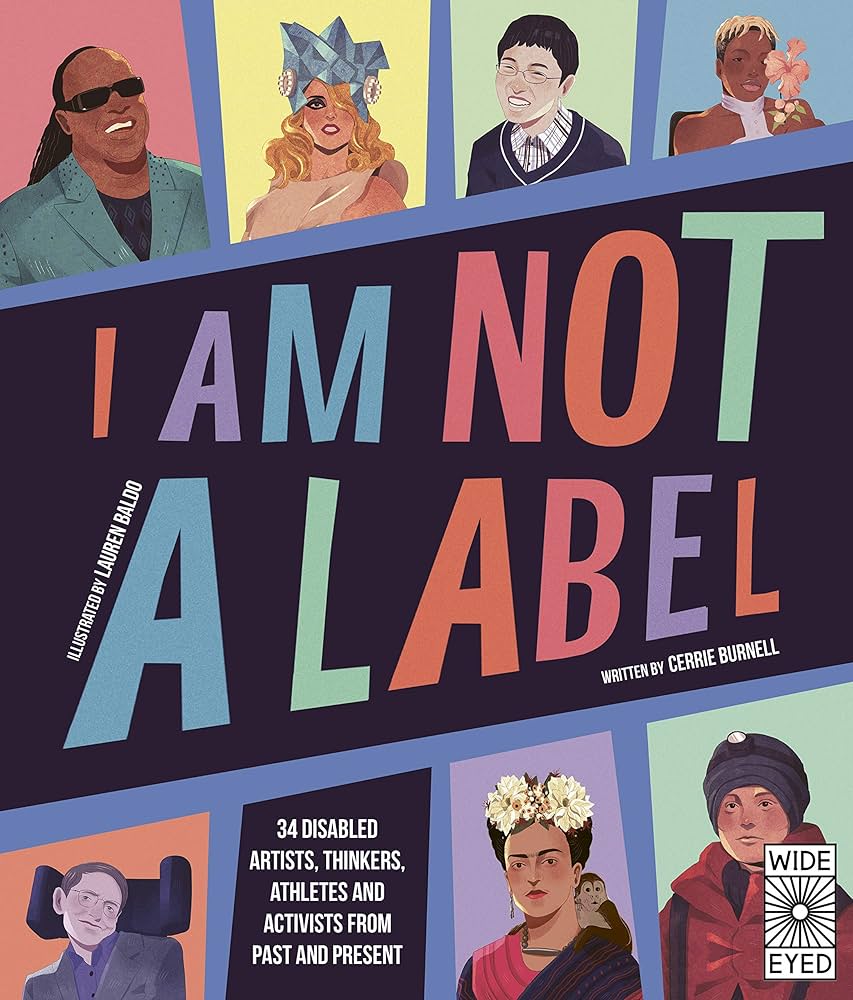

📗 I Am Not a Label by Cerrie Burnell Nonfiction | Illustrated Biographies | Age 8–13 Summary: Biographies of global figures with disabilities, including Indian personalities. Encourages readers to rethink exclusion and celebrate diverse identities.

Bibliography:

- Ambedkar, B. R. (2002). The Essential Writings of B.R. Ambedkar (V. Rodrigues, Ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Natarajan, S., & Anand, S. (2011). Bhimayana: Experiences of Untouchability (Illustrated by D. & S. Vyam). Navayana.

- Talbot, I., & Singh, G. (2009). The Partition of India. Cambridge University Press.

- Thapar, R. (1997). Ashoka and the Decline of the Mauryas (Rev. ed.). Oxford University Press

Leave a comment