Content Warning: This article discusses depression and suicidal ideation.

It’s Lonely at the Centre of the Earth (2023) is an autobiographical comic by Zoe Thorogood that made her a 6-times nominee for an Eisner Award. In this review, I discuss the relevance in her depictions of mental health and selfhood within her autobiography.

I have always been a very strict reader. I have early memories of being about 9 years old, struggling to read Harry Potter because it was all my friends were talking about, but much to my dad’s disappointment, fantasy was never much my thing. I was drawn to very specific, fictional characters and storylines: the weirder the better.

As much as I loved reading, I very rarely stray from fiction. When it comes to non-fiction, I strictly stick to essays. No self-help is allowed. And if there is any theory to peruse in my bookshelves, it will most likely be on education, queerness, and feminism. Above all, you’ll never find a book with someone’s portrait on the cover. I do not read biographies. At least, not ‘regular’ biographies (cue the ‘cool mum’ sound from Mean Girls. I am getting so old). I do think there is a use for biographies. My disdain for them is more complex than simply not liking them; it is also embedded in very subjective political views of the publishing industry that are a topic for another day.

Regardless, I do have a soft spot for bio-graphic-novels. Using mixed media to portray a personal story is a bold and vulnerable decision, and has proven to be very successful within the industry: Funhome (2006) by Alison Bechdel; Persepolis (2008) by Marjane Satrapi, and Maus (2003) by Art Spiegelman are some of the most famous biographical comics to date, and are often referenced in academic discussions. Some more recent texts still cause trouble within US-American school libraries, such as Gender Queer (2019) by Mia Kobabe, not only for its LGBTQ+ representation, but for its explicit references to sex and menstruation.

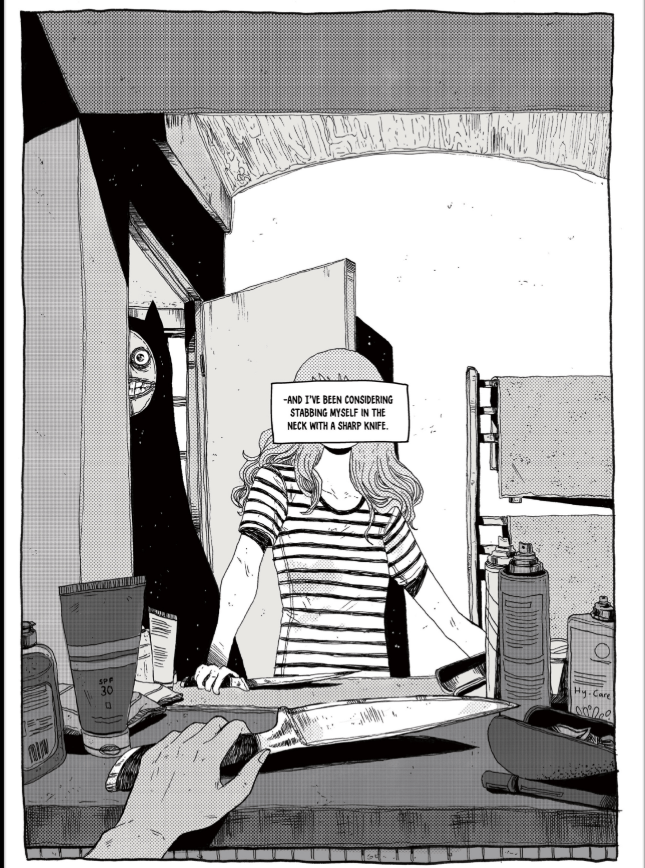

The book that inspired me to write this article has nothing on Kobabe’s. It is not particularly explicit or graphic for my taste, but it does deal with depression, self-harm and substance abuse. It’s Lonely at the Centre of the Earth (2023) is an auto-bio-graphic-novel Zoe Thorogood wrote while she was 23 years old. Zoe Thorogood’s debut graphic novel The Impending Blindness of Billie Scott (2020) had a massive success, and this susequent autobiography addresses the anxiety of ‘what’s next’ after an acclaimed novel while dealing with depression and suicidal thoughts in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Because of the contents, some graphic portrayals, and themes within the comic, I have to make this explicit: This comic is not appropriate for children under the age of 16. It is, however, a very compelling and possibly relatable story for young adults (yes, people in their early 20s do classify as young adults).

As I mentioned before, using the graphic medium to tell a personal story allows for a different text-reader relationship.

It requires other ways of communicating from the author, and active interpretation of text and image from the reader, giving this narrative, which holds a heavy emotional weight, multiple layers for the reader to dissect and understand the protagonist.

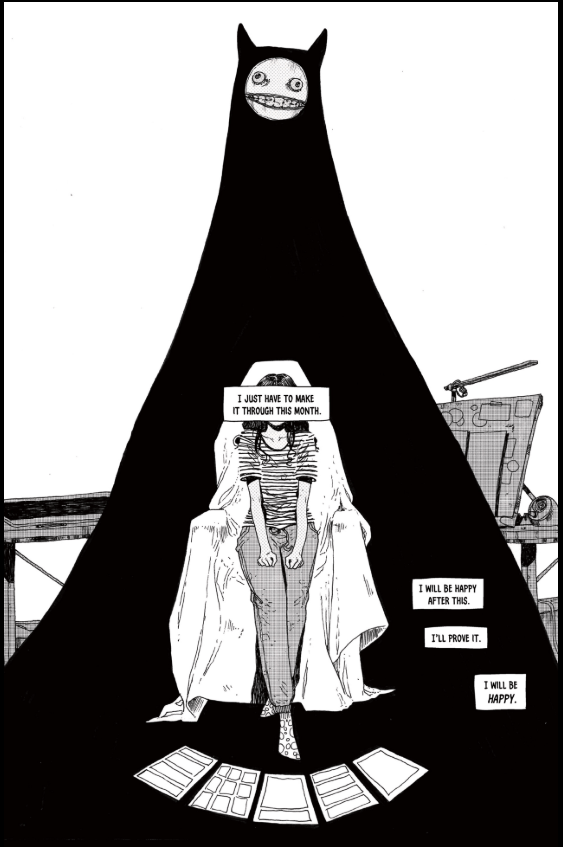

The literary scholar and comic expert Hillary Chute explains that ‘it makes readers aware of limits, and also possibilities for expression, in which disaster, or trauma, breaks the boundaries of communication, finding shape in a hybrid medium’ (2017, p. 34). Thorogood’s representation of personal conflict and self-doubt is often portrayed as a group discussion with different representations of herself, letting the reader in on her internal debates. Through these different representations, Thorogood shows not only multiple aspects of herself, but her own self-perception (see Peters & Horsman, 2025), as well as the looming presence of depression, making itself more visibly present in panels as Thorogood faces different dilemmas. This is further emphasised when her suicidal ideation is the most prevalent.

Shaping a narrative and coming of age

Although this is a biographical text, it can also be read as a coming-of-age story. After all, Thorogood deals mostly with her own identity and how she relates to the rest of the world in terms of relationships, career, and coping with the weight of existing while being depressed. I highlight this to show the varied and deep possibilities of this text. Not only is it a personal account, but it also touches upon issues that are, or can be, crucial during developmental stages, such as: What am I doing with my life? This is especially relatable for people who have already finished high school, are officially in their 20s, maybe going to university, where their relationships start to shift as everyone attempts to deal with adult life for themselves.

Shaken by the vividness of her suicidal ideations, and the threat she presents to her own life after her debut graphic novel was published, Thorogood devises a plan for herself: To record the next six months of her life, employing career events and social occasions as opportunities for character development – all to be documented in her graphic autobiography.

Throughout the comic we see Thorogood attempt her best at presenting a classic coming-of-age story: She’s at an all-time-low, but a trip to the U.S. for a Comic Con. panel, and connecting with a fellow artist (which she hopes to be a romantic interest) can help her get through this period. But real life is not a script, so due to COVID her flight gets cancelled, and although she does meet with her fellow artist, things are not running as smoothly as she had hoped – he is a father of two, still very much in love with the kids’ mother, and NOT emotionally available.

As Thorogood recounts her story, and how she has to constantly re-think her initial plot plans, she invites the reader into her creative process. Most times, it is a subtle break of the fourth wall, showing aspects of her creative process, discussing the meaning of art, her own purpose, the satisfying feeling of physically seeing your progress in ‘the stack’ of pages you’ve completed, and so on. These moments, mixed with the more emotionally brutal ones make Thorogood’s voice feel authentic and vulnerable in a refreshing way. Her style of writing and sharing content is a clear example of why she is often labeled as ‘relatable’, something she was not initially fond of.

‘I don’t know how I can be ‘relatable’ when I feel like an alien in human skin’ (Thorogood, 2023)

As someone who has been dealing with depression for most of their life, I don’t like to read about it. Most times, I find narratives about depression to be repetitive and misleading, recycled and overused phrases about ‘carrying on’ appear too often and harmful behaviour is straight up romanticised and justified for the purpose of the narrative and the character’s perceived doom.

In Thorogood’s case, the reflective qualities of her biography mixed with her art show how subjective yet visceral dealing with depression can be. She does not tip-toe around the topic. The first page of this graphic novel shows nine panels of our protagonist dancing with earphones, accompanied by Thorogood’s witty introduction, pointing towards the cliches of a coming-of-age movie: ‘It’d be a slice of life drama, maybe a romcom at a push. It’d be about the highs and lows of your average nobody […], but this isn’t a movie-’ (Thorogood, 2023, p. 1), and delivers the punch with the page turn:

The reader can see from the very beginning that this is definitely not a light-hearted read. The reality of mental health is hardly palatable for a lot of people, and yet, Thorogood manages to communicate these feelings by balancing art and silence, because what is most telling in these situations, is what she omits from the narration. But that is also a highly interpretative exercise on the reader’s part, my part, filling in those moments with my own experiences of self-harm and suicidal ideation. However, regardless of the reader having such experiences themselves, these spaces can and most likely will inspire empathy on the side of the reader. Thorogood’s relatability shines on her own depiction of herself, vulnerably realistic, and possibly one of her harshest critics at times.

‘You’re teenage girls. Statistically, it’s going to happen’ (Thorogood, 2023).

Thorogood recounts her experiences living with and around depression. From early on in the book she states that she has had suicidal thoughts since she was 14 years old, how it ‘runs in the family’, and how depression has continuously been in her life in different ways. She recalls how authority figures who were in charge of her wellbeing basically told her to ‘suck it up’. As far as my personal memories go, as a very depressed young girl, I have had experiences where my depression was openly disregarded or overlooked, but this would have made me explode.

I deeply empathise with this story because I see a lot of my own experiences reflected.

More often than not, my depression can be paralyzing, but when interacting with my family, it becomes something else altogether. Overall, as a young girl I was often catalogued as a shy girl, who sometimes got overly heated when debating (if you consider respect for basic human rights and dignity up for debate) and would have ‘just needed a pick-me-up, a boyfriend, or simply a better attitude’.

Maybe it’s a cultural difference, maybe it’s just part of being a teenager during the 2010s, but depression was not a word I seriously considered until I turned 20, and even then, I don’t think my family genuinely understood what it meant until they had to take charge of the most basic parts of my treatment because I was a risk to myself. Otherwise, the need to isolate and the disabling anxiety were considered a bit of an overreaction, and a manifestation of being sensitive, as a lot of my family members would describe themselves.

I mention this because of how normalised it all felt to me as a teenager, and still does in many ways today. Thorogood manages to capture the dread of how it feels to be in a depressive episode around close family. She depicts the tension over simple interactions, and what it feels like to be the reflection of things that your family members would rather not address within themselves, because more often than not, it is a genetic trait.

Making sense of the world

I highlight this graphic novel not only because of the impactful depiction of mental health, but also because I appreciate Thorogood’s final reflections on a natural breakthrough that took determination to keep struggling while persevering with treatment. (let me just note here that self medication is NOT treatment.)

‘Loneliness makes it hard to see the bigger picture. It makes you self-obsessed, not out of narcissism but because your own self is all you have. Your flaws, quirks, regrets, and mistakes begin to engulf you […]. I’m slowly starting to realise that when my brain proposes suicide, what it really means is it wants to go someplace else, where it can exist formless and free, where times flows differently and thinks make sense.’ (Thorogood, 2023)

Zoe Thorogood also uses her Instagram account to share smaller comics, art, and news about her next projects. She has been openly talking about the importance of mental health, her own struggles with mental health after her brother’s passing, donating part of her earnings to different mental health foundations, and her current project called ‘It took my brother.’

If you or someone you know is struggling with depression and suicidal ideation, information and resources are available at Therapy Route.

Bibliography

Primary text:

- Thorogood, Z. (2023). It’s lonely at the centre of the earth: This book is for someone, somewhere: an auto-biographic-novel. Image Comics.

Secondary sources:

- Chute, H. L. (2017). Why comics? From underground to everywhere (1st ed.). Harper.

- Peters, M., Horsman, Y. (2025). The Autographic Gesture and Narrative Identity. In: Autobiographical Comics and Graphic Novels. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-92257-2_2

Leave a comment