This piece explores the lived realities of Dalit and Indigenous children in India, whose lives and struggles remain largely absent from dominant narratives. It examines how education, often framed as a tool of emancipation, fails to include their histories, voices and experiences, instead reinforcing exclusion within supposedly liberatory systems.

The idea of “lived experience” has become increasingly common in both research and public discussions (Hoerger 2016). This rise is linked to the growth of identity politics and to the limits of traditional academic disciplines in understanding the realities of marginalised people. Thinkers such as phenomenologists and feminist scholars have long spoken about lived experience, but their theories often try to fit people’s experiences into fixed, universal categories. These categories usually come from dominant cultures, which decide what kind of experiences are seen as valid and whose voices are heard.

In India, the idea of lived experience becomes especially important when we look at the history of caste. The caste system is rooted in the ancient varna and jati divisions. It has created a strict social order based on ideas of purity and pollution, which dates to more than 3000 years ago, and still exists. (Reddy 2005)

According to unofficial estimates, as many as 1.3 million Dalits in India are still employed as manual scavengers, cleaning dry latrines with their bare hands and without protection. It is an occupation that places them at the lowest rung of the caste hierarchy. At the bottom of this rigid social order, the children of manual scavengers bear the full weight of the stigma.

This article honours the Dalit children of Kollangarai, Tamil Nadu, who were recently stopped from using a common mud path on their way to school. The incident brings to our attention caste abuse and obstruction that still exists and continues to actively shape our immediate surroundings.

© India Today, 2025. All rights reserved.

It makes starkly visible how the childhoods of marginalised children have long remained absent from popular discourse. The insurmountable weight of trauma carried by those who have known discrimination since memory itself, reveals how early one learns to negotiate the world. These children adapt not out of choice but necessity. They learn resilience before play, caution before curiosity. Their lives unfold within a continuum of struggle, where the pursuit of agency, access and the ordinary joy of a “normal” life becomes a lifelong act of resistance.

In Limbda, Himachal Pradesh, the death of a twelve-year-old Dalit boy confined within a cowshed, accused of “polluting” a house, has made news. This is one among the countless incidents that usually go unreported, unrecognised and unacknowledged. Yet this one has surfaced, momentarily, into public view.

Dalit children have become inheritors of a long struggle for access and dignity. They continue to encounter the invisible architectures of caste that contour everyday life. The terrain of childhood has become a living archive of resistance.

Underprivileged children are often celebrated as proof of inclusion, yet their very presence exposes the rigid hierarchies of the educational order. One example is the recent success of nine students belonging to the Onge tribe, who, for the first time since India’s independence, passed the CBSE Class 10 examinations. While this may appear to be a milestone in the story of inclusion, it is imperative to remember this success cannot be mistaken for the system’s success. Instead it gives rise to darker questions. What does this success mean for a community that has long lived at the edges of India’s social imagination? For children whose language, land and traditions find no place in the syllabus that now defines their achievement? The system celebrates their entry into its fold, but it does not change to meet them.

It demands instead that they adapt. It reveals instead the immense labour required of children who must translate themselves to be legible within institutions that do not accommodate them. For the underprivileged and marginalised, intelligence is not the question – compatibility is. They must step into classrooms built without them in mind. Their belonging is conditional on adaptation. Education here demands their transformation before offering recognition. The curriculum, the medium of instruction, the codes of discipline; all assume a universal child who never was them. What appears as progress is not. Children belonging to marginalised communities therefore begin to distort themselves until their discomfort becomes invisible. They try to excel within a framework that was never designed to even consider their lived realities.

The burden of inclusion falls on the child, who is forced to perform in a language beyond their reach while schools refuse to adapt to their realities. The system does not fail because these children lack ability – it fails because it cannot imagine such an existence. Classrooms and textbooks continue to speak a language that leaves their lives outside its margins. What is celebrated as inclusion often becomes a quiet form of erasure. In the name of equality, they must learn to belong by becoming someone else. Their achievement, while remarkable, reminds us that education in its present form still struggles to hold space for every child’s truth.

“Even as they learn to conform, master the language of the state, and excel by the system’s own standards, the space they enter remains structurally closed to them.”

Philip G. Altbach’s argument becomes crucial here, as he reminds us that academia itself is a contested space. If academic freedom is under attack even for those within the mainstream, then what future awaits those who stand at its margins? Even if these children learn to conform and excel, they may still find no real place in academia. Even as they learn to conform, master the language of the state, and excel by the system’s own standards, the space they enter remains structurally closed to them. The freedom to think, speak, and exist on their own terms is denied to them long before they arrive there.

In schools, they are routinely made to perform cleaning work and face daily humiliation. One Dalit girl recalls, “I used to sit in the front row of my class, but the students complained that they were getting polluted. So the teacher made me sit at the back… when I was in grade 6, unable to bear it anymore, I dropped out. I wanted to become a nurse or a doctor. But now all my dreams are broken.” Reports by Navsarjan Trust, including Voices of Children of Manual Scavengers and Understanding Untouchability, document these realities across Gujarat. This makes us aware of how teachers, local authorities and communities continue to impose discrimination and forced labour on Dalit children despite laws banning untouchability. While national statistics show declining dropout rates overall, the gap between Dalit and non-Dalit students continues to widen; a reminder that exclusion persists beneath the facade of progress.

So what does a child belonging to a marginalised background do in India? They are shunned by their peers, if they even manage to access the classroom space. Their teachers become the very instruments through which casteism is reinforced, shaping young minds to inherit and repeat prejudice. The systems meant to protect them treat them as disposable.

While mental health is increasingly being discussed in the country, what place does the mental health of a Dalit child occupy in these conversations? The onus is entirely on the child to maintain immense and impossible mental strength through such ordeals. Here, it is important for us to not get carried away with praising Dalit children’s “strength”. While this strength is indeed commendable, it is also tragic; for why must a system require its children to be so strong merely to survive? Is resilience here a natural trait, or an unavoidable necessity forced upon them from birth?

Community psychology within Dalit, Bahujan, and Adivasi contexts thus becomes crucial to any honest discussion on mental health. The “agency” of a Dalit child is often nothing more than the burden placed on them to keep engaging with structures that deny their humanity. They carry suppressed trauma that has been passed down. These are the silent consequences of being born into a caste society that refuses to see them as children first. Why must they fight so hard from the moment they are born? What happened to a childhood of dreams, hobbies, wishes, and play? These children are made to grow up far too soon, their innocence traded for endurance. There are no easy answers for the countless lost childhoods that can never be recovered.

The documentary India’s Forgotten Children, exposes the brutal realities of trafficking and systemic oppression faced by Dalit children across the country. Yet despite such documentaries existing, and despite extensive research and fieldwork, their truths remain largely absent from mainstream discourse. The filmmakers identify education as the only sustainable path forward, but education itself continues to be inaccessible; and when accessed, is often an oppressive tool. The irony is unmistakable: the very system presented as emancipatory is the one that reproduces exclusion.

A troubling pattern also persists in the knowledge economy surrounding Dalit lives. Much of the scholarship and commentary on Dalit childhoods comes from savarna academics. While their work may stem from good intentions and self-reflexive recognition of privilege, the question remains—where are the voices of Dalit scholars, educators, and children themselves? Why must others continue to speak for them instead of creating space for them to speak from their own experience and epistemology? This is not to dismiss the contributions of those who have written passionately on caste injustice, but to expose the quiet continuity of a system that claims to democratise education while still determining who gets to author its narrative.

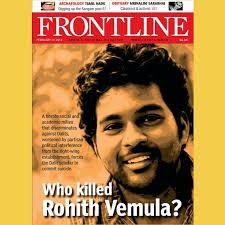

What happens when Dalit children do make it to higher education in such a system? What becomes of them then? Rohith Vemula’s institutional murder becomes crucial in understanding this question. Vemula, a doctoral student at the University of Hyderabad, was subjected to targeting and hostility from his university faculties. He was stopped from talking about his experiences, and ultimately suspended for his activism. His death should be correcly described as institutional murder, which occured in 2016. It exposed the deep, structural caste violence embedded in Indian higher education. His death was not an isolated tragedy but a revelation of how caste operates within universities. The same universities that claim to be spaces of equality and free thought. Through Vemula’s death, the silence around caste in higher education was momentarily broken. Conversations about discrimination, exclusion and mental health briefly surfaced across campuses.

It raises a troubling question that forces a hard look at privilege. How many of us hold nostalgia as a gentle inheritance of childhood – the foods we tasted, the games we played, the television shows that shaped our evenings, the songs we grew up listening to? Yet, how often do we pause to think of the childhoods that unfolded parallel to ours, marked not by memory but by denial? What does it mean to inhabit a world where innocence itself is stratified, where some childhoods are preserved as sentiment, and others are erased just for existing?

All the labour that goes into becoming something, into creating a space for oneself in an institution, can be undone in a moment.

Yet the tragedy lies in what his story represents: that even after years of perseverance and resilience, the system can still deny dignity. All the labour that goes into becoming something, into creating a space for oneself in an institution, can be undone in a moment. It shows how, for many Dalit students, education does not necessarily guarantee freedom, it just becomes another site of struggle.

Bibliography

- Hussain, A. (2025) ‘Elderly woman hurls caste slurs, blocks Dalit students from using common mud path’, India Today, 25 September.

- Navsarjan Trust, Center for Human Rights and Global Justice and International Dalit Solidarity Network (n.d.) Dalit children in India – victims of caste discrimination. Available at:https://idsn.org/wp-content/uploads/user_folder/pdf/New_files/India/Dalit_children_in_India_-_victims_of_caste_discrimination.pdf

- Parashar, S. (2025) ‘Limbda torn apart after death of 12-year-old Dalit boy’, The Indian Express, 8 October.

- People’s Watch (2025) ‘Stubborn for a cause: How a Dalit mother is waging a war to let her son rest in peace’, People’s Watch, 2 September.

- Reddy, D.S. (2005) ‘The ethnicity of caste’, Anthropological Quarterly, 78(3), pp. 543–584.

- Lawson, Michael. (2014) India’s Forgotten Children [Film]. Available at:https://www.youtube.com

- The Hindu Bureau (2023) ‘Caste atrocity blamed for 16-year-old Dalit boy’s death in Pudukottai’, The Hindu, 17 November.

- Shankar, K. (2016) ‘Who was Rohith Vemula?’, Frontline, 3 February. Available at: https://frontline.thehindu.com

- Zubair, S.A. (2025) ‘Beyond milestone: What Onge students’ CBSE success reveals about India’s tribal education’, Maktoob Media, 16 October.

About the author

V Vidya is a Master’s graduate, driven by a deep interest in ethics, human rights and equity. She worked as a Research Assistant on a UNICEF WASH project at Bharathidasan University’s Centre for the Study of Social Inclusion, where she contributed to research, documentation and report writing. Her academic work has always engaged with caste—whether through examining its cinematic portrayals, studying iconography, or exploring how art and culture reflect structures of power and resistance. She believes that true equality is intersectional and that real progress begins with acknowledging those who are most marginalised.

Outside her research, she loves painting, reading, and follows Formula 1. A dedicated fan of Lewis Hamilton, she admires his courage, and his consistent use of his platform to stand up for the underprivileged and marginalised—values that inspire both her work and worldview.

Leave a comment