Knitting has traditionally been depicted as an old, white grandma’s cosy activity. Anabelle, an assertive and independent girl, shows in Mac Barnett’s picturebook Extra Yarn that knitting can be, in fact, a tool for standing her ground and re-shaping the community.

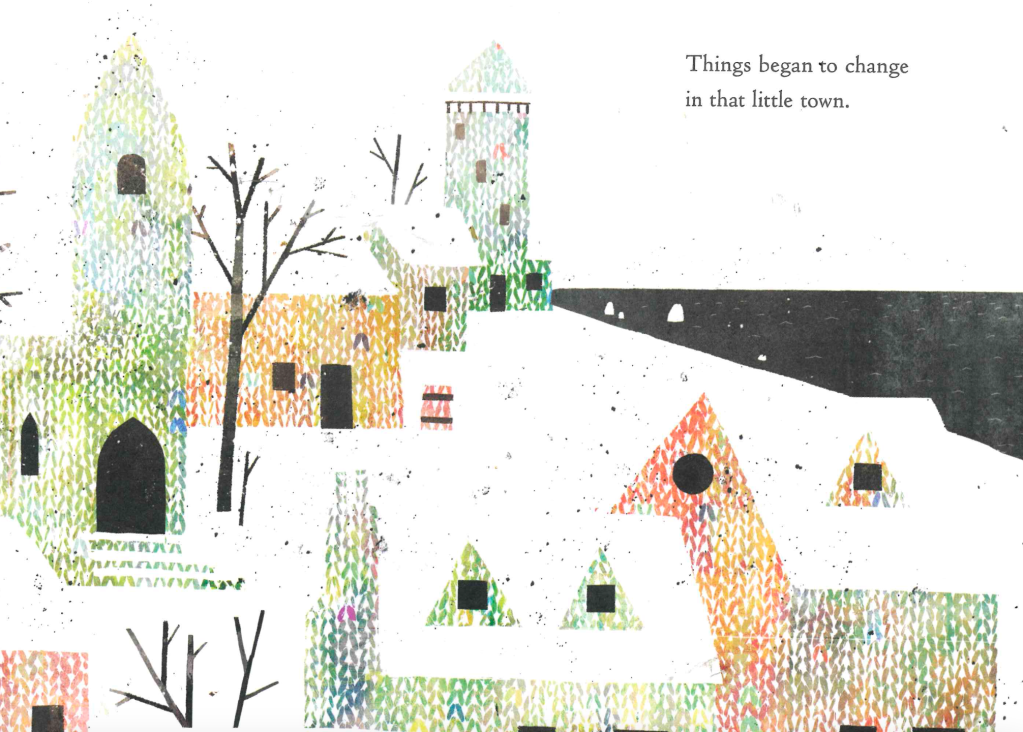

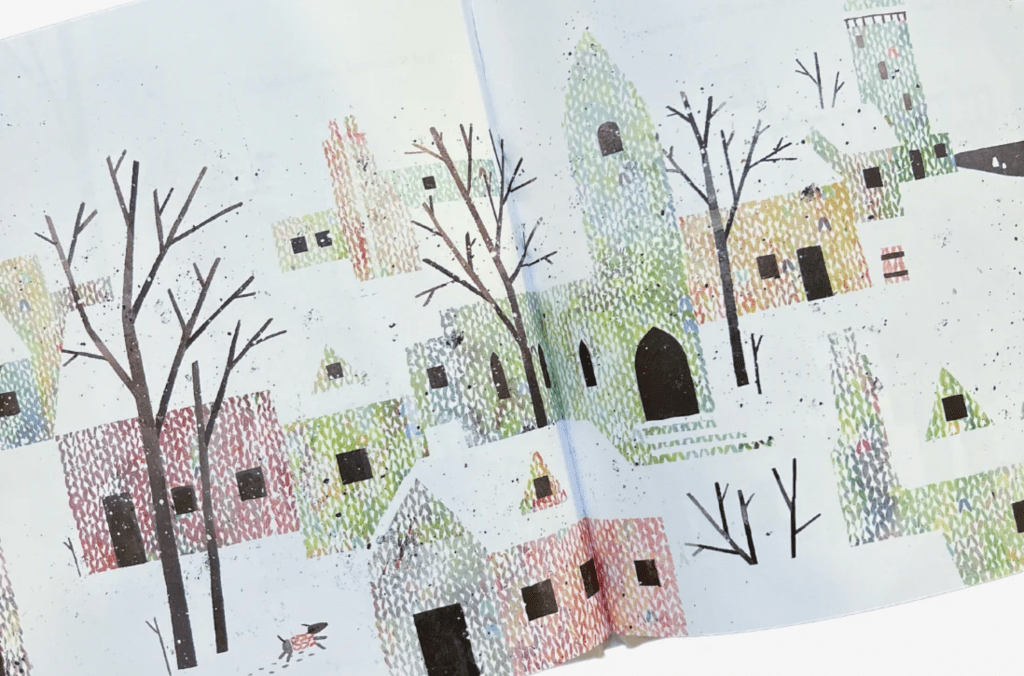

If I had to describe the plot of the picturebook Extra Yarn by Mac Barnett (illustrated by the wonderful Jon Klassen, 2013), I would summarise it like this: Anabelle finds a box of infinite multicoloured yarn and decides to knit a sweater for herself and another one for Mars, her dog. When Luke makes fun of her sweater… she makes one for him and his dog. When Mr. Norman tells Anabelle off for distracting the rest of the class with her really colourful jumper, she replies that she will knit one for each person in the classroom. He defies her, saying that she can’t possibly knit that much. But he is wrong, and soon her classmates and even her severe teacher are warmly covered in the colourfully striped yarn. This goes on until the whole town is dressed in stockinette stitches garments (including the buildings).

© Mac Barnett, Jon Klassen and Walker Books

The mere summary of seemingly repetitive events do not do justice to the book and the topics behind Anabelle’s yarn venture: She shows great self-assurance, highlights the value of initiative within community and portrays agency enactment.

To understand why Anabelle’s actions are so groundbreaking, we must analyse the ideas around the value of yarn and knitting. According to Jones (2022), textile crafts have been historically understood as a benign and calm pastime for old ladies. Moreover, Robins (2022) affirms that this stereotype has highly impacted the way in which these crafts, particularly knitting, have been perceived. In consequence, they have not been regarded as an art or even as a hobby for wider audiences; they have been treated as a token of appreciation by relatives (as if affection was not crucial in human interaction…) and nothing more. However, Robins is adamant in pointing out that knitting is, in fact, for everyone and has an expressive potential: understanding it as a powerful medium for self-expression aids in subverting the narrative of old-white-lady activity and exacerbates the significance of non-stereotypical uses of knitting. In other words, through knitting we can communicate with others, interact with our surroundings, and re-signify the activity itself.

The subversive character of Anabelle and her sweaters come from the fact that she is not silent, not old, not yet a woman but a girl, and she does not knit because that is what is expected from her – she knits motivated by her affection for the community and by her desire to change things in the small town. As a knitter, she is not silent and self-effacing, but the contrary. She is strong-minded, opinionated and does not fear standing up for what she believes is right.

The subversive character of Anabelle and her sweaters come from the fact that she is not silent, not old, not yet a woman but a girl, and she does not knit because that is what is expected from her – she knits motivated by her affection for the community and by her desire to change things in her small town.

Not only the knitting activity itself is a statement in Extra Yarn, but the infinite colourful yarn that Anabelle finds and uses has meaning as well. Against a cold, black and white world, choosing to dress the people, the animals and the buildings in warm and colourful garments is activism. Anabelle is prompting, all by herself, one stitch at a time, the change she thinks her community needs while respecting their personalities and boundaries (like Mr. Crabtree, who smiles with his hat amid the snow after telling the girl that he does not use sweaters).

The story of a girl with a magic box of yarn extends well beyond Anabelle’s town, and so people from all around the world travel to see her marvelous sweaters and to shake her hand in awe. Her fame, however, brings an ill-willed fashionista to the shores, who wants nothing else than the miraculous yarn. Even when the Archduke offers one, two and ten million pounds for it, Anabelle says no. She will not sell the yarn and, more significantly, she will not crush her beliefs for money.

The aristocrat does not take the negative very well, which leads to a plot for stealing the yarn amid the darkness of night. He escapes with the magic box, not considering Anabelle’s refusal, her right to self-determination and feelings. The Archduke only cares for himself. The opposition between individualism and community surprises him once he arrives at his grey and lonely castle: the box only contains a pair of used knitting needles, nothing else.

The reader, in consequence, concludes that the box was never the source of Anabelle’s endless knitting projects, but her sheer determination to warm her community and build a more colourful town (with all the inclusive connotations of this adjective) was. In a rage fit, the Archduke throws the box through the window. The box floats on the sea, among ice fragments, directly to Anabelle, who grabs it. Inside, she finds her old needles and her infinite yarn, corroborating the previous interpretation.

Children’s agency and power are highly valued in Barnett and Klassen’s signature subtle way. Reading Extra Yarn makes us believe in the power of a single person to change the attitudes of those around her. Not only that, but it also shows us readers the potential of art and crafts to promote positive changes in the community. As Anabelle, we can support each other through subversive warmness and affection within a cold world and make a soft change, one stitch at a time.

Leave a comment