While Van de Vendel and Tolman’s Vosje (2018) is widely praised for its luminous illustrations and endearing protagonist, this article argues that beneath its beauty lies a subtle yet powerful anti-curiosity and father-knows-best narrative.

The child has become what James (2009) calls a ‘social actor’—an active participant shaping and influenced by their social world. This means that the child is recognized for their active influence on their social domain, even though they depend on adult care. According to Berlyne’s concept of ‘epistemic curiosity’, children’s curiosity play should include “components of problem solving, exploration, and productive activities.” Chak (2007) explains that this development of ‘epistemic curiosity’ is fostered by teachers’ encouragement of “parents to promote children’s curiosity through everyday activities, by supporting them to explore, experiment, discover and find out for themselves”.

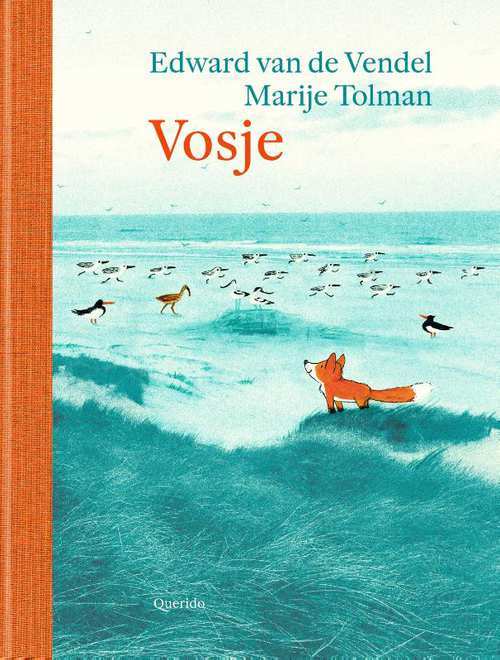

This article discusses the agency of curiosity through a short case study of one of my favorite picturebooks ever: Edward van de Vendel and Marije Tolman’s Vosje (2018). The story follows Vosje’s (Translation: Little Fox) exploration of the boundaries between curiosity and safety. The picturebook starts when Vosje follows two purple butterflies through the dunes. He falls hard and loses consciousness. He starts to dream about his life: from his earliest memories in the den, outside adventures with his sibling and a curious human child, all the way up to the moment of the fall. Will Vosje ever wake up again?

The first thing that stands out when picking up the picturebook is Tolman’s unique art style. She created this experimental look by illustrating realistic animals and a fluorescent orange fox atop muted, blue-toned Riso-printed photographs of dune landscapes in the Netherlands. In De Grote Vriendelijke Podcast, Tolman explains that she takes the photos on her iPhone. She elaborates that professional cameras made the photos too stiff, unlike the spontaneous phone pictures. The images are also unedited and do not feature human-made elements. The muted color makes the natural backgrounds less distracting. The fox’s neon color was chosen for the same reason: to make the character stand out. The choice of mixed media reflects the duality between realism and imagination while reading her picturebooks.

The Dutch picturebook became widely popular after its release, has been translated into fourteen languages (Chinese, English, French, German, Italian, Lithuanian, Macedonian, Persian, Polish, Russian, Slovakian, Slovenian, Spanish, and Turkish), and won various prizes including the Zilveren Griffel for the best children’s book (2019), the Zilveren Penseel for the most beautifully illustrated children’s book (2019), and and inclusion in the White Raven catalogue (2019).

The many positive reviews highlight elements such as the high-contrast illustrations, the lovable little fox, and the story’s appeal across ages. Reviewers have called the picturebook powerful and endearing, a cute story about growing up and caring for one another, but also completely lacking a moral. Even though the majority of these reviewers disregard the aspect of agency and even curiosity, the author discusses his intentions. In an interview, Van de Vendel said that he wanted to show the risk of playfulness and curiosity while also including the delight it can bring to a child’s life. Thomas de Veen offers a similar reading to the author’s intention. Unlike other reviewers, he recognized the dangers of curiosity portrayed in the picturebook. Still, his overall conclusion is that the positive results of curiosity – including trust, love, courage, and encounters with new human and non-human animals – overarch the story. Additionally, reviewer Jaap Friso writes about the necessity of balance within the dichotomy of alertness and open-mindedness, safety and adventure, and dream and reality.

While I appreciate loving and hopeful books and agree with many reviewers, I propose a different reading of the picturebook’s contents in relation to agency and curiosity. More specifically, I also want to counter-argue an anti-curiosity moral within the picturebook.

Central in the case of curiosity is “the relationship between structure (the organization and regulation of society) and agency (the individual’s right to, and possibly of, acting independently).” The notion of hierarchy enables and restricts the child’s agency (James 43). In the case of Vosje, the paternal authority is the structure, and Vosje’s curiosity represents the agency. The picturebook repeatedly includes the father’s phrase that roughly translates to curiosity will kill you. Through his dream, the reader learns that Vosje fails to understand the meaning of his father’s warning, which occasionally gets him into trouble. On the first occasion, Vosje gets his head stuck in a glass jar after trying to discover its contents. He gains an understanding of his father’s warning, yet this does not stop him from curiously following the butterflies later. On the one hand, there is the overarching voice of the father (the structure), on the other hand, there is an agentic little fox who deliberately chooses – and has the opportunity to – ignore these warnings. Yet the anti-curiosity, and therefore anti-agency, reading from the text is present in the ending. The book concludes with a father-knows-best narrative where Vosje decides to refrain from following butterflies again. In a sense, the picturebook portrays a non-human animal “becoming” through its idea that Vosje is exploring the wonders of the world before presumably growing up into a responsible adult like his parents. Vosje’s encounters with negative results of his “epistemic curiosity” could suggest that the child is better off within the safety of parental protection, and while the story ends on a positive note, the reader could be left to wonder if Vosje’s curiosity was worth – nearly – dying for.

In conclusion, Vosje illustrates the ongoing tension between safety and curiosity in children’s agency. This duality raises the question of whether the story promotes exploration or obedience. While the father warns his child, the little fox still has the agency to explore. The child reader is not merely a passive recipient of the text’s ideology; the overarching moral may encourage the child to explore or to reinforce the idea that a child should always listen to their parents. To not finish on this critical note, I want to encourage you all to pick up this book and enjoy the incredible art of Tolman and the beautiful text written by Van de Vendel. Though this article provided a counter reading of the common interpretation, Vosje is an adorable picturebook about exploration and curiosity. It also teaches that while you may not always make the right decision, most unfortunate situations sort themselves out. It may just remind you not to chase those purple butterflies again.”

Bibliography

- Bakker, Miriam. “Vosje.” Boekmama, 6 Oct 2019, https://boekmama.nl/vosje/.

- Chak, Amy. “Teachers’ and Parents’ Conceptions of Children’s Curiosity and Exploration.” International Journal of Early Years Education, vol. 15, no. 2, Jun. 2007, pp. 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760701288690.

- Christensen, Nina. “Picturebooks and Representations of Childhood.” The Routledge Companion to Picturebooks, edited by Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer, Routledge, 2018, pp. 360-370.

- De Veen, Thomas. “Wordt nieuwsgierigheid het vosje fataal?.” NRC, 18 Oct 2018, https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2018/10/19/wordt-nieuwsgierigheid-het-vosje-fataal-a2635077.

- Friso, Jaap. “Vosje.” JaapLeest, Accessed 5 Jun 2024, https://jaapleest.nl/vosje/.

- James, Allison. “Agency.” The Palgrave Handbook of Childhood Studies, edited by Jens Qvortrup, William A. Corsaro, and Michael-Sebastian Honig, Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, pp. 34-45.

- Judith. “Vosje – Edward van de Vendel & Marije Tolman.” Biebmiepje, 21 Feb 2019, https://biebmiepje.nl/2019/02/21/vosje-edward-van-de-vendel-marije-tolman/.

- “Maar de tekenaar heeft er een olifant van gemaakt.” Interview by Jacoline Maes & Guus van der Peet. Vooys, 2020, pp. page 51-57.

- Van Geem, Daniel. “Recensie: Vosje en de vogels en het jongetje” Athenaeum, 12 Nov 2018, https://www.athenaeum.nl/recensies/2018/vosje-en-de-vogels-en-het-jongetje.Van de Vendel, Edward. “Vosje.” Edward van de Vendel, Accessed 5 Jun 2024, https://www.edwardvandevendel.nl/boeken/vosje.

Leave a comment