The 2021 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) Report examines how well children are reading in 57 countries and eight benchmarking entities. This infographic summarizes its main results, highlighting trends and factors that influence how young people read.

They say old habits never die. The moment we chose as a team to talk about literacy my mind immediately went to think about the existence of data related to it. I was almost sure that the one available would be related to the classical approach of reading literacy without considering the multiple ways and media through which humans interact to express and narrate their culture.

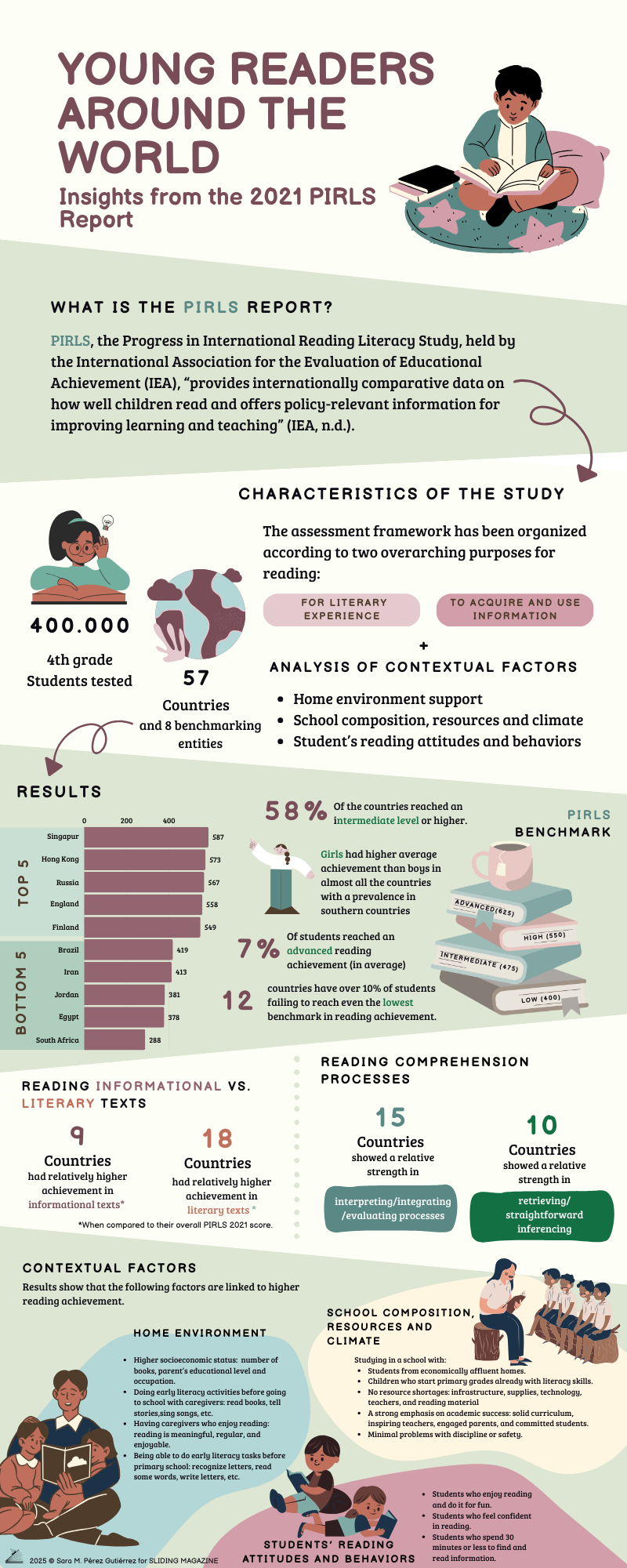

Curious, I began researching and discovered that in 2021, the most recent Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) was conducted. This large-scale assessment evaluated the reading literacy levels of 400,000 fourth-grade students across 57 countries and 8 benchmarking entities.

The PIRLS 2021 assessment framework defines reading literacy as “the ability to understand and use those written language forms required by society and/or valued by the individual” (TIMSS & PIRLS, 2021). Viewing reading as a cultural necessity for constructing meaning and participating in society, 18 passages where chosen to evaluate two main purposes of reading— reading as a literary experience and reading to acquire and use information— and four dimensions of comprehension: focusing on and retrieving explicitly stated information, making straightforward inferences, interpreting and integrating ideas and information, and evaluating and critiquing content and textual elements.

The selected passages were designed to be age-appropriate, engaging, and culturally unbiased, with particular care taken to avoid problematic representations related to gender, race, ethnicity, or religious beliefs. Once chosen, the texts were submitted to the participating countries for review and approval. This process not only ensured that the material reflected the kinds of readings students typically preferred, but also verified—where applicable—that translations have not compromised the clarity or the potential enjoyment of the texts.

PIRLS 2021 was the first of these studies to be administered in both paper-based and digital formats. In both cases, students received a booklet containing two texts with varying levels of difficulty. Besides the reading assessment, students, parents, principals, and teachers were asked about their perceptions and experiences regarding contextual factors that may influence children’s reading habits and literacy. These factors included the family’s socioeconomic level, parents’ educational background, literacy activities before starting school, types of reading instruction, availability of school resources and technologies, and students’ reading habits both inside and outside of school, among others.

Who Reads Better?

The PIRLS Report offers a snapshot of children’s reading abilities worldwide, guiding educational policies but also revealing global inequalities. When reviewing the results by region, the highest scores are observed in countries from Asia and Western Europe, Oceania, and certain regions of Canada and Russia. In contrast, the lowest performances were mainly recorded in the Middle East, the Balkans, Central Asia, Latin America, and Africa.

These results reflect the ongoing debate between rich and poor countries, raising the question of whether countries are wealthier because they read, or whether they read more and better because they are wealthy.

Beyond the Books: What Surrounds Reading

The contextual factors analyzed confirm the hypothesis that higher reading achievement is strongly associated with a more favorable socioeconomic background. Key elements include having better-educated parents, access to books and technology both at home and at school, well-qualified teachers, and attending schools with greater resources and stronger social capital. Reading literacy is also deeply influenced by caregivers’ ability to engage children in activities that foster reading skills, an aspect that can be difficult, if not unattainable, in households where caregivers have limited time or resources to dedicate to such practices.

What Is Still Missing?

Even though the assessment framework considered many elements to be as inclusive as possible, these indicators still carry the bittersweet reminder of methodological limitations, as they cannot fully reflect the diversity of students and schools.

For instance, children with cognitive or learning disabilities, as well as those attending remote schools, were excluded from the assessment. This highlights the need either to adapt the framework to integrate these groups or to design a differentiated strategy to ensure their realities are also represented and taken into consideration to design national educational policies.

Challenges Ahead

Although the new PIRLS results will be published in 2026, the number of participating countries has increased to only 61, with Latin America still underrepresented (Brazil is the only country from the region assessed). As this will be the first study conducted entirely online, concerns arise regarding how differences in digital literacy are being measured and the potential impact these differences may have on the results. Assuming that children worldwide are digitally literate is a serious mistake.

Since PIRLS relies on nationally representative samples, it is unrealistic to expect that all schools or families will have access to the necessary technological equipment or that students regularly use such tools. Therefore, when considering the inclusion of more countries in this study, paper-based assessments should be taken into account once again.

Reading: A Right Still Pending

With only a quarter of countries being measured, the results continue to highlight the importance of early access to both analogue and digital reading materials in helping children communicate their world and understand the one around them. In this sense, while in many countries the debate centers on “what should children read?”, in others the more pressing questions remain “how can we get them to read?” or “what will they read?”.

There is still a long road ahead to ensure that children everywhere have the opportunity to hold a book or learning material in their hands and to grow up in contexts that value and promote literacy.

As children’s literature scholars and promoters, we must remember that our field is not only about discussing what stories are told or how they are represented. It is also about facing the reality that most children never have the chance to access the artistic and literary creations we celebrate.

Yes, there are still many stories waiting to be told. But before that, we need to ask ourselves how we can make sure every child has the means, whether through books, digital tools, or community spaces, to narrate their own world.

Bibliography

- TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center and International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) (2023) PIRLS 2021 International Results in Reading. Amsterdam: IEA.

Leave a comment