This article explores Capernaum and The Colors of the Mountain, two films that portray “adultified” children in impoverished and violent environments. Their symbolic objects—a passport and a soccer ball—embody both resistance and resignation in their pursuit of having the right to be children.

The streets of Beirut and the mountains of Colombia. Rampant poverty and rural violence. Two boys, Zain and Manuel. Two natural actors and two documentary-like films: Capernaum (2018), a Lebanese film directed by Nadine Labaki, and The Colors of the Mountain (2010), a Colombian film directed by Carlos César Arbeláez. When portraying impoverished, vulnerable children, there is often a tendency to romanticize their capacity to endure or recover from hardships. Hope is intrinsic to their journey of growth. However, these two films, even while depicting highly resilient children, ensure that the ultimate takeaway is the systematic way in which society fails them, annihilating every attempt to live fully as a child.

In this oppressive environment, unprotected, surviving children have an apparent freedom to engage in actions that, in other contexts, would typically be reserved for adults. However, these actions are, in reality, mechanisms of adaptation. This excessive capacity to act places them in a state of extraordinary agency, where the only visible remnants of their childhood are their still-developing bodies. This forced extraordinary agency adultifies them, compelling them to cling to symbols of hope as reminders that, someday, they might finally be allowed to experience childhood.

SPOILER ALERT: From this point on, the article will discuss certain plot details. If you’d like to experience the movies first, feel free to pause here and return later.

Capernaum (2018): Growing Up Too Soon

Capernaum (2018) shows that Zain’s extreme poverty is not merely monetary. Through his parents, we see how their poverty represents an intergenerational trauma that has denied them the ability to perceive themselves as subjects of rights. It is the conviction of being trapped in an eternal cycle of poverty that leaves Zain’s parents in a state of incomplete adulthood, hindering their ability to act as providers and negotiators of their limited agency to reshape the future of their family. Zain’s parents’ resignation to their incomplete adulthood leads to their defective parenthood, where Zain has little opportunity to feel and perform as a child. His embodied childhood is only invoked by his parents when control is required, yet it is disregarded when it comes to adult responsibilities, such as working or, in his sister’s case, raising a family. This leads Zain to the streets, where he learns its codes and how to survive. Hunger drives him, but the desire to care for his sister propels him forward, making him eager to learn the multiple ways to protect her childhood and address her additional gendered challenges. The protection of his sister Sahar’s childhood is an act of hope — a desperate attempt to reclaim his own lost childhood and break free from the cycle of neglect that has defined their lives.

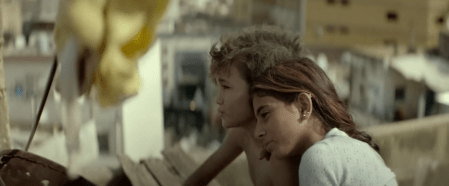

But hope seems to be ephemeral in an adultified child. His extraordinary agency — the agency of an adultified child — has its limits when it comes to preventing his parents from giving his young sister to an adult man. The undeniable atrocity of this situation, even in a cultural context where such practices are still common, leaves Zain with no options. His hope, his claim to childhood, becomes impossible. Returning to the streets, which seem to offer more protection than his parents, becomes a feasible and familiar choice. When he meets the Ethiopian migrant worker Rahil and her toddler Yonas, Zain smiles again. Still in extreme poverty, Zain provides protection for Yonas, and in return, he finds shelter, food, and experiences of care that are both new and unfamiliar to him. It is as if, just as he positioned the silver tray to reflect the neighbor’s cartoon program, he manages to find a place to see childhood reflected — even if just for a limited time.

But this glimpse of hope ends when Rahil is imprisoned, and Zain must again assume the role of primary caregiver. The dangers feel more imminent, but he continues to repeatedly choose to remain on the right side of the balance, caring for the child. When he learns that there is still an option — through the acquisition of a passport and a chance to migrate to Europe — Zain does what he has been taught: selling opioid-laced water in the streets. But when he realizes that he has been evicted from Rahil’s place, losing all the savings he had hidden there, Zain surrenders. He acts as the adults around him have, and sells Yonas to the human trafficker, Aspro.

The passport, now his new symbol of hope, takes him back home to ask for his identity papers. “Nobody cares about you or us,” says his father, Selim, after confessing they never registered any of them. Their lack of legal existence as citizens not only delays his plans to leave but also leads to his sister’s death as she cannot access emergency services when giving birth.

What option does an adultified child have when every shred of hope is taken away? To become an adult. What does an angry, powerless, and mourning brother do? Kill his sister’s husband. Zain tried to reclaim his childhood, to access it. But in the end, he returns to society as the adult they forced him to be.

The Colors of the Mountain (2010): War and the Right to Play.

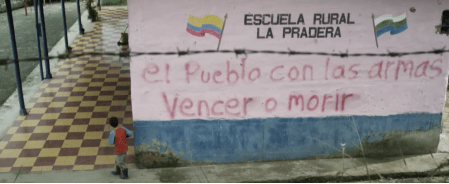

A similarly harsh reality where childhood is constantly undermined is presented in The Colors of the Mountain (2010). Manuel lives in a completely different family context. He resides in a remote Colombian farming village, where his father works the land, and his mother manages the household. Amid a territory contested by the guerrillas and paramilitary forces, Manuel and his friends learn to live by, respect, and accept the codes of war. Their games are quiet down whenever guerrilla fighters are nearby, and they don’t dare to reclaim control of their soccer field from them. However, living in the countryside allows them to move freely around nature, even amid the risks.

Like most Colombians, soccer is the primary recreational activity for Manuel and his friends. When his parents gave him a brand-new soccer ball and goalkeeper gloves as a birthday present, Manuel knew he had acquired a new level of popularity and power in his group. When they play their first picadito — a fastpaced match with friends — the soccer ball rolls down the hill. Before retrieving the ball, they help a farmer corral a monumental pig that escapes and runs towards the place where the ball landed. Unfortunately, the pig is sent flying into the air and tragically dies after stepping into a landmine.

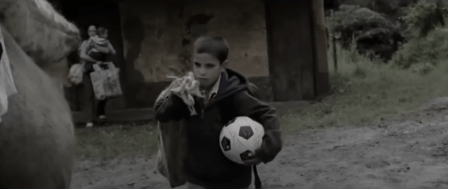

From there on, the film follows Manuel and his two friends as they try to rescue the soccer ball from the now dangerous field. Although this drives Manuel’s actions, we also see the adult backdrop: the struggles of providing proper education, the propaganda and hate discourses propagated by each armed force, the recruitment of minors for war, the threats that Manuel’s father faced for attempting to be ideologically independent, and his subsequent murder. The soccer ball becomes not only a memory of his father but a symbol of the belief that his right to play is worth the risk of his life in a landmine-filled field. What else can they take?

A Passport and a Soccer Ball: Holding on to Hope, Memory, and Resistance

At the end, Zain gets his passport and Manuel his soccer ball. When taking the passport photo, Zain is asked to smile, and he does. When Manuel climbs into the stake truck, surrounded by other displaced farmers, we see how quickly his gaze shifts from the vibrant colors of the mountain to the black-and-white shades of the soccer ball he holds in his arms. The passport and the soccer ball symbolize liminal elements of hope in these children with extraordinary agency. On the one hand, they represent the reassurance of always finding a way to sustain childhood and to claim the right to live this phase according to their embodied developmental expectations. On the other hand, they serve as reminders of their departure from home, its causes, the hardships they had to endure, and the heartbreaking idea that hope might be turned away once again.

Bibliography

- Arbeláez, C. (Director). (2010). Los Colores de la Montaña Film]. El Bus Producciones.

- Labaki, N. (Director). (2018). Capernaum [Film]. Mooz Films.

Leave a comment