Join this first-person account of the Kunstmuseum Brandts’ exhibition of the 80 tea-stained, original pieces behind Danish cartoonist Jakob Martin Strid’s bestselling picturebook Den fantastiske bus (2023). Their raw, unfinished nature allow insights into the 15-year creative process behind this one-of-a-kind 2.5-kilogram masterpiece.

If you are expecting a review of the plot of Jakob Martin Strid’s Den fantastiske bus (2023) (translated to English as The Fantastic Bus), then you are at the wrong place. This is a review of the Danish cartoonist’s craftmanship and creative process; an insight into the place that children’s literature holds in the Danish artistic scene; and a first-hand retelling of my experience encountering the large-scale original drawings that constitute this bestselling work of art.

Den fantastiske bus: what and for whom?

It is difficult to class Den fantastiske bus into a fixed category. Is it a picturebook? Yes. Is it a masterpiece? Also yes, but is it a literary or a (visual) artistic one? Who is its target audience? Despite being classified under children’s literature, its 2.5 kilograms of weight, material difficulty to handle, and over 200 pages of length challenge the idea that this book is aimed at young readers for their independent reading and enjoyment. Adults – or a joint venture of adults and children – may be better suited to revel in the artistry behind each double spread and fully grasp the themes of imagination, community, and adventure that the book centres around.

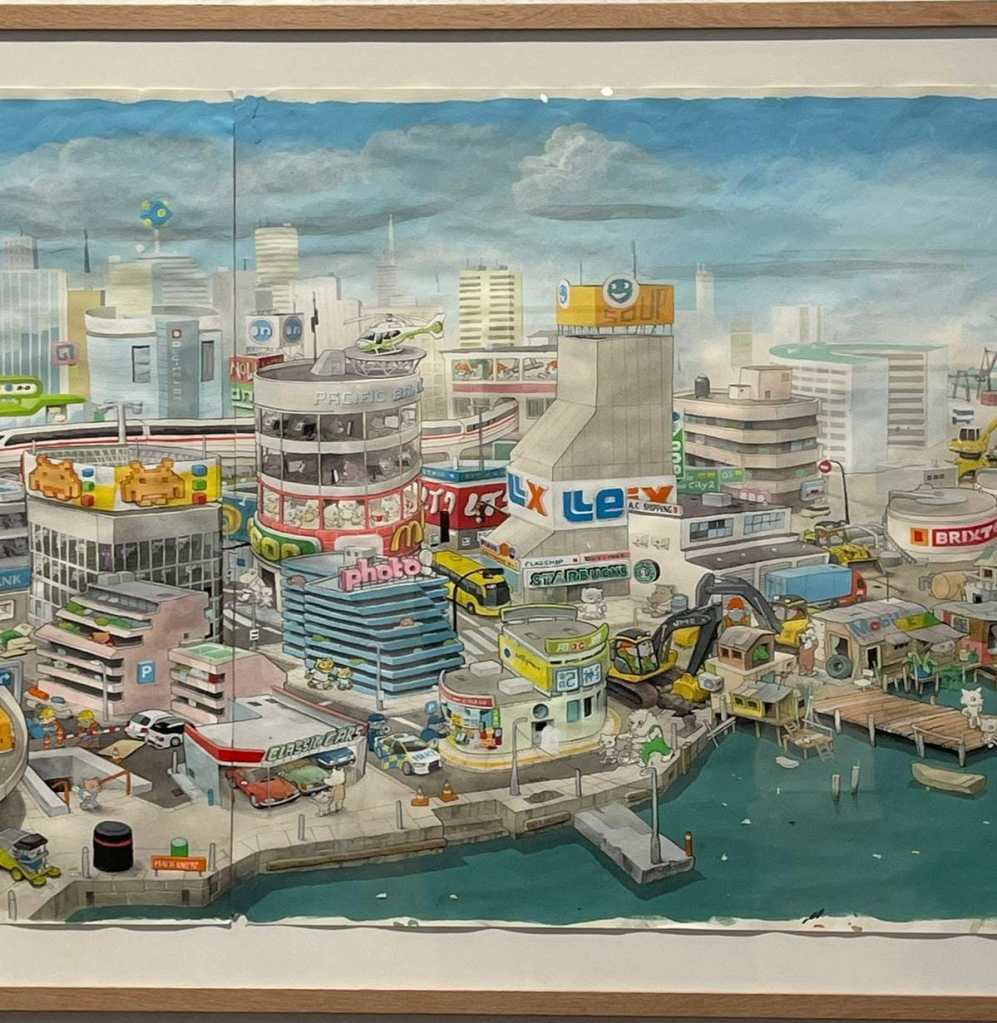

Being transparent – I have not read the book in whole. I have only skimmed through its pages and can only tell you little about the plot. Anthropomorphised animals living in a harbour-side community of slums build a magical bus to embark on a journey to the land of Balanka, in order to obtain a saffron lily that may save their sick friend’s life – endangered due to air pollution. To me, the exhibition does not aim to highlight the plot of the picturebook or focus on the literary aspects of Strid’s work. Instead, it is a call to value the craftmanship behind a picturebook, often undervalued in terms of artistic merit compared to other artistic expressions. A year-long exhibition like this, featuring the work of a children’s author and illustrator at a state-recognised art museum in Denmark, speaks of the place that children’s literature has in the country. Having won the Nordic Council’s Children’s and Young People’s Literature Prize in 2024, Strid is situated in the national landscape and venturing into the international one, with his book being published in France, Norway and China with many more countries having bought its translation rights (Glydendal, 2024).

Children’s literature in the public eye

Whether Strid’s success is determined by children’s positive responses to his books, or adult’s aesthetic appreciation of his visual artistry is an interesting question to pose, especially considering that his pieces at the exhibition are displayed at eye-level of an adult. However, the opening of an exhibition in a cultural space such as the Kunstmuseum Brandts can spark debate and increase visibility of children’s literature, an often silenced and underappreciated literary and artistic field. It can show non-children’s literature enthusiasts the scope that picturebooks have when they are directed to a dual audience, or the exhaustive process behind producing a high-quality, heavily illustrated children’s book.

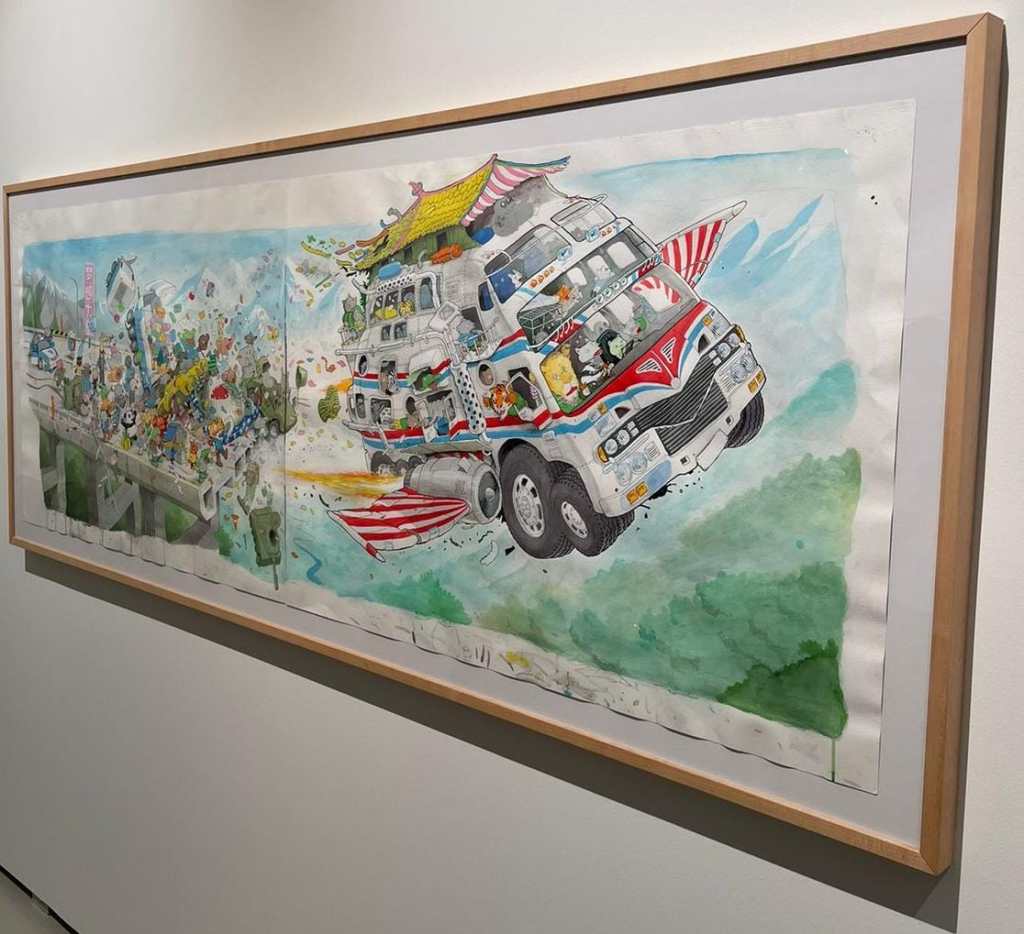

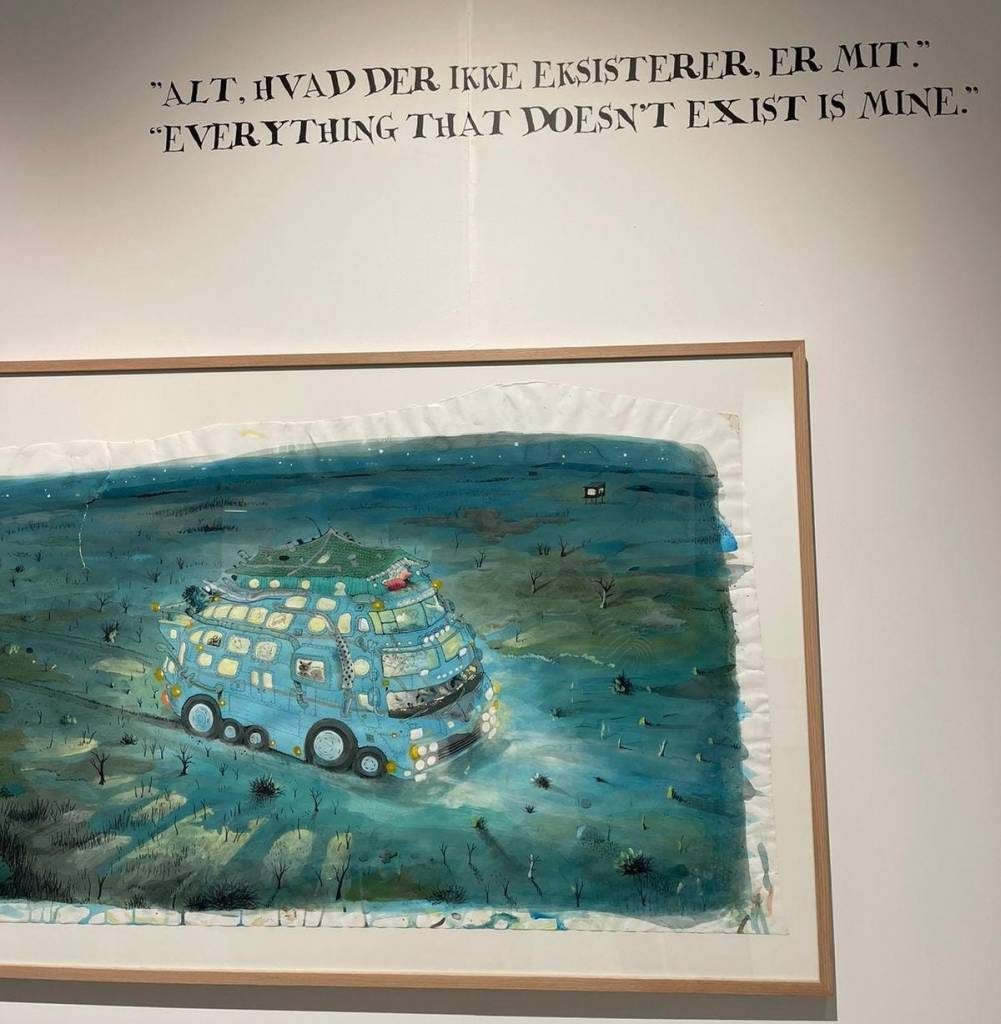

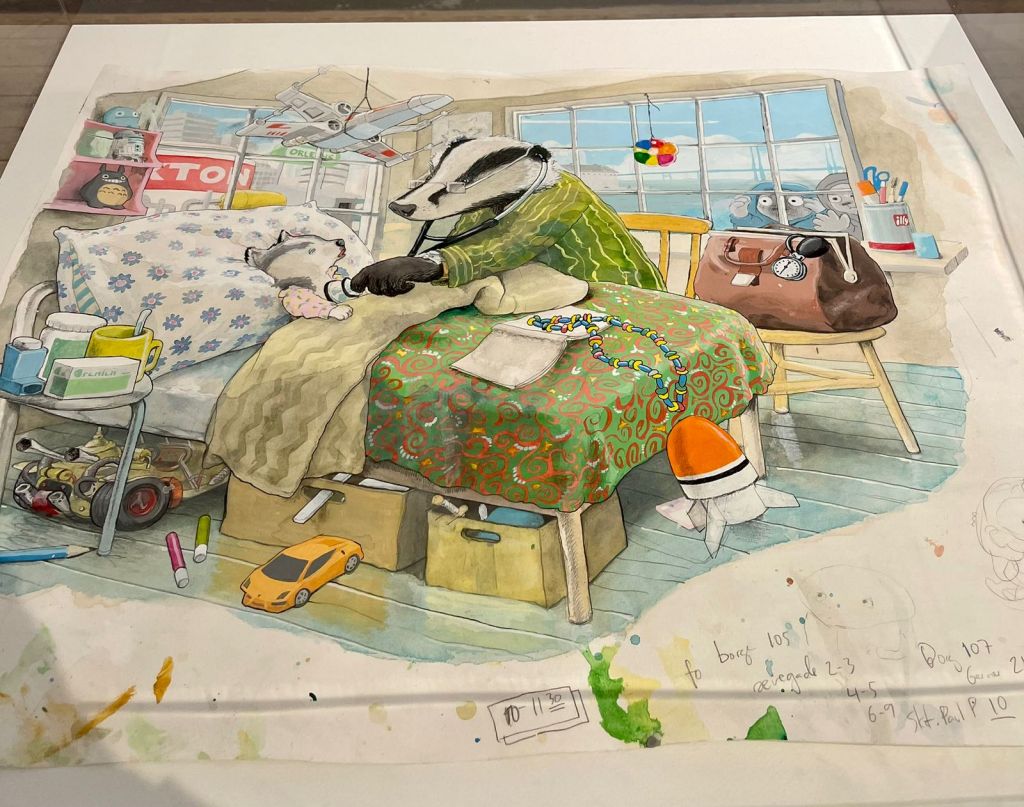

The exhibition itself is divided into two rooms in accordance with the two parts of the picturebook. With exhibit labels being close to none, and some quotes sprinkled around the framed drawings, the museum invites its visitors to enter a fantastical watercolour realm where hours can be spent looking at minuscule details of each piece. Over 80 full-size original drawings, in thin brown frames can be seen. In addition, models of the fantastic bus have been incorporated in the exhibit, including one made out of Lego (of course! It is Denmark after all).

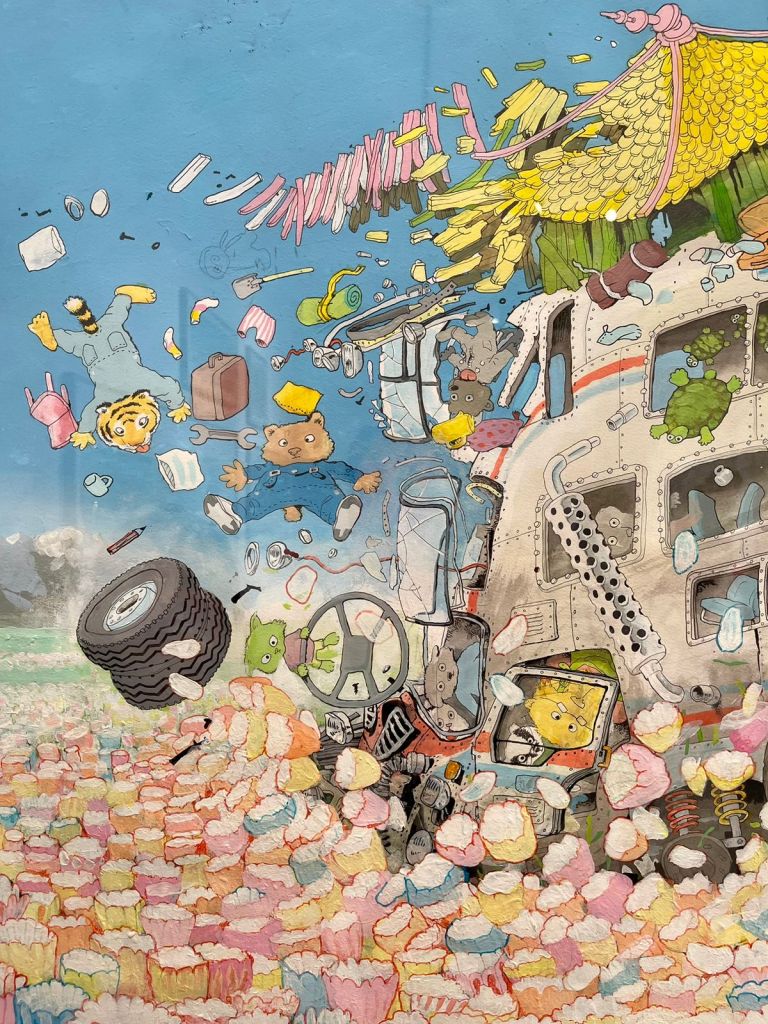

The mood changes between the two rooms comprising the exhibition. The first one focuses on the first part of the picturebook where the characters are set against a harbour city, living in what could be classed as a slum or commune. Ahnstarr City holds resemblance to harbourside parts of Copenhagen, while also being a megacity that could be found in Southeast Asia with its skyscrapers and abundance of neon signs and advertisements for banks, telecommunication companies, and fast-food restaurants (a familiar red and yellow “M” can be seen in a jam-packed double spread). Illustrations of slum interiors, with their lack of light and mismatched decor, contrast with the commercialised big city environment and the building of the magic bus, where a lot of attention is paid to the intricate mechanics behind its construction. The second room focuses on the trip and arrival to Balanka, adopting a more dreamlike quality in terms of illustrations and storyline. Darker blues, milky pinks, and yellows build on the fantastical quality that the storyline takes on, distancing itself from the harsh, grim reality that is presented in the initial spreads set in Ahnstarr City.

Phone numbers, teared-up canvases, and unfinished sketches

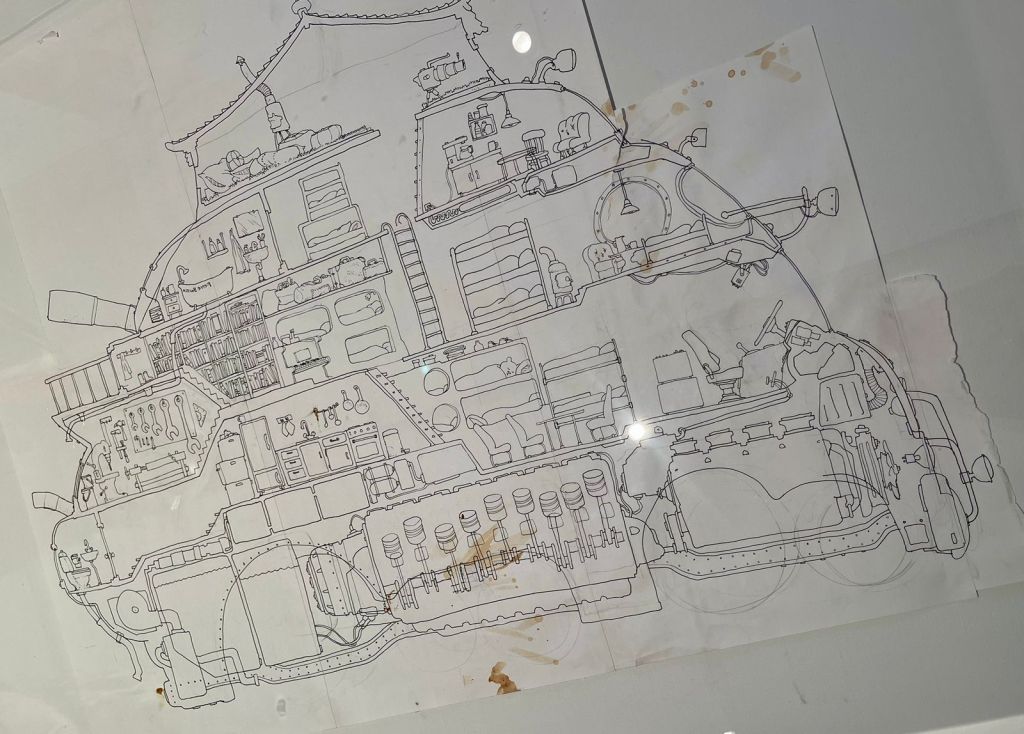

Strid’s artistic process flows where his pen takes him, so often several pieces of paper are pieced together or cut out in a slapdash manner.

The real life-sized drawings that constitute the book’s illustrations have been left almost untouched. Strid’s artistic process flows where his pen takes him, so often several pieces of paper are pieced together or cut out in a slapdash manner. Liquid stains, telephone numbers, and other seemingly random pieces of writing populate his drawings. The museum staff told us visitors that, when searching who a phone number scribbled on the margins of a page belonged to, a locksmith’s contact came up – pointing towards the mundane nature of Strid’s approach to writing the picturebook, where pieces of information unconnected to the plot tell stories of the artist we are encountering. Wear and tear seem to be another character in Strid’s work, communicating messages about his artist persona and his view on art.

Unfinished and uncoloured sketches have been included in the curation, as well as pieces that do not feature in the final version of the picturebook. The editing of the illustrations, from their analogue to digital version, is made tangible throughout the exhibit. The unruly borders of the pieced together pieces of paper have been hidden, and colours have been made more vibrant; a shock when encountering the original illustrations for the second half of the book and seeing how much deeper and darker their colour palette was. Maybe less engaging and capturing of a young reader’s eye, the less saturated illustrations encountered in real life made me adjust my eye and take time to explore their visual appeal as a painting of Monet’s water lilies or a still from Miyazaki would have.

Finding these incomplete objects recurringly made me think of Strid’s creative process and wonder if – mid-drawing – he changed his mind or simply got bored with the task at hand and decided to focus on another part of the illustration, leaving their edition for future stages of the book’s production.

I found myself playing a game with Strid, following a “Where’s Wally?” pattern with his unfinished sketches of characters and objects. These partially complete elements are often hidden in the original drawings, amidst complex scenarios featuring the bus with many animal characters and mismatched objects flying out of windows into the sky. Finding these incomplete objects recurringly made me think of Strid’s creative process and wonder if – mid-drawing – he changed his mind or simply got bored with the task at hand and decided to focus on another part of the illustration, leaving their edition for future stages of the book’s production.

Leaving the exhibition, I was left with a great desire to create something myself. The documentation of Strid’s creative process made me want to play around with different mediums and media, without the pressure of it being perfect the first time around. Despite his unmatched craftmanship in his use of pen, ink, and watercolour, the raw quality of his work permeates the exhibition, and his 15 year-long creative process is inspiring for people in and out of the children’s literature field; young and old. At different levels, most people can relate to and appreciate parts of Strid’s work as presented in the process behind Den Fantastiske Bus. Plot-driven or illustration-oriented admirers, detailed observers of the intricate scenes or searchers of intertextuality, mechanics fanatics or art critics all have a space in this exhibition.

Bibliography

- Grøn, T. (2023). Den fantastiske bus ved godt selv, den er fantastisk. Politiken.

- Tvegaard Andersen, S. (2024, October 22). Jakob Martin Strid vinder Nordisk Råds Børne- og ungdomslitteraturpris 2024. Glydendal.

Leave a comment