It is rare for museums to devote space to children’s cultural artefacts, but recently the Museum of Literature Ireland has curated two exhibitions highlighting the value of children’s and YA literature.

When preparing for my recent trip to Dublin, I was looking for attractions and museums in the city when I came across the Museum of Literature Ireland (MoLI). I decided it would be the perfect final destination, along with a stroll in Saint Stephen’s Green, to unwind after a long day of exploring.

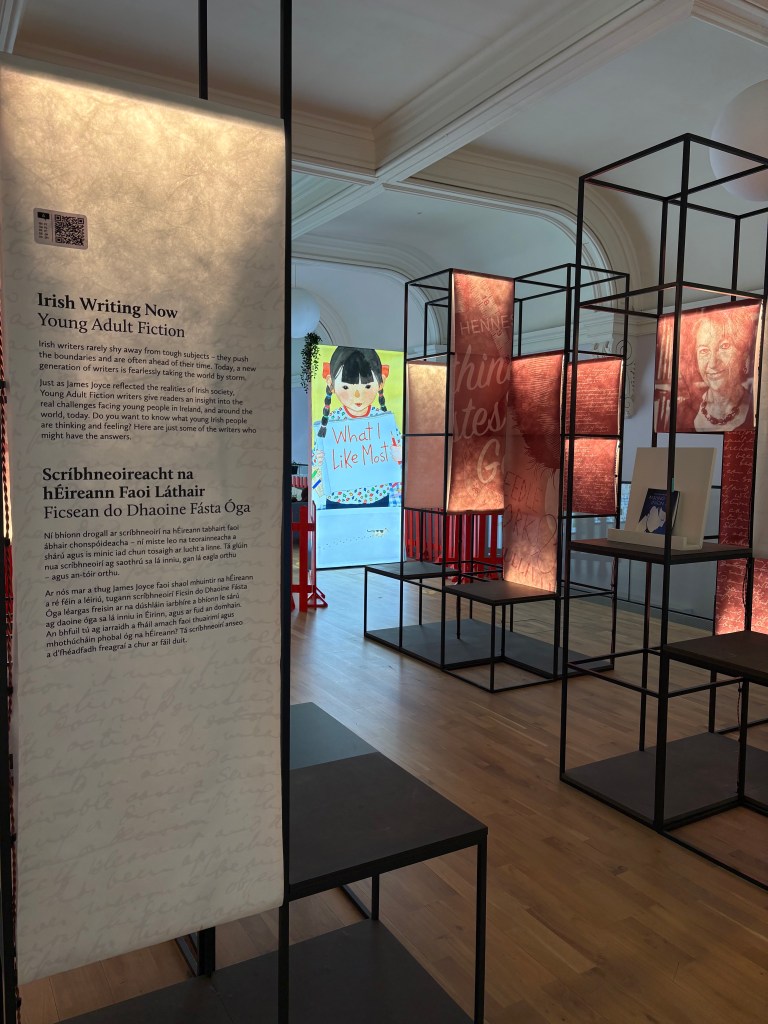

I must confess that I did not do any research beforehand about the museum’s exhibitions. I was sure I would encounter Beckett, Shaw, Wilde, and Joyce there, and that was more than enough for me. I was pleasantly surprised when, in addition to the mentioned authors, a section on the upper floors was dedicated exclusively to Young Adult Fiction in the “Irish Writing Now” exhibition and to the picture book What I Like Most by Nancy Murphy and Zhu-Cheng Liang.

The “Irish Writing Now” exhibition showcases contemporary Irish authors who have decided to explore different genres for a young adult audience, some of them in Irish and others in English. Several panels, with two authors each, create a spatial composition that allows you to explore each one of them freely and learn about the writers and their novels. They introduce you to Éilís Ní Dhuibhne and Deirdre Sullivan, who compose emotional narratives linked to family, changes, distress, and moving forward; to Derek Landy, Darren Shand, Claire Hennessy, Dave Rudden, Sarah Maria Griffin, and Louise O’Neill, who create fantastic worlds in which their protagonists must find themselves among complex (and sometimes dystopic) societies; and finally to Peadar Ó Guilín, who writes a modernised version of Irish mythology.

The only Irish YA writer I knew before my visit was Eoin Colfer from my joyful read of the Artemis Fowl series as a teenager, and some of his graphic novels like Illegal, co-written with Andrew Donkin and illustrated by Giovanni Rigano, which I have read now as an adult. This curation is an invitation to discover the words that authors from outside our immediate context have to offer to us. I was personally drawn to O’Neill’s Only Ever Yours due to its ferocious critique of the media’s obsession with women’s perfection, which is still a problematic issue – and a relatable one.

I did however miss some artefacts related to the books to accompany the text, as well as some information about their editorial process. The described stories are interesting, but the audience’s curiosity can easily be lost among the many titles mentioned. Engaging visual elements can help visitors to hold their attention, and they might even inspire them to choose a novel from the curated selection to read.

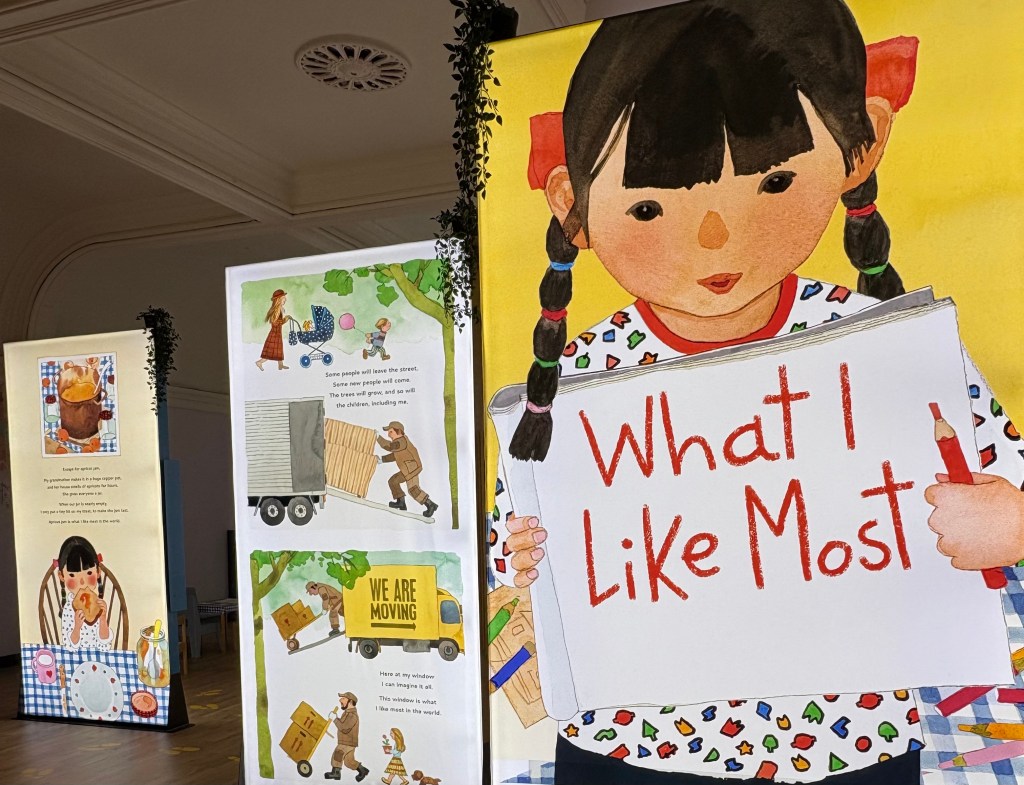

In the other half of the section, the temporary exhibition presents What I Like Most in big bright panels that must be read following the path of the yellow footprints on the floor. This immersive experience requires the audience to navigate through the picturebook’s pages to enjoy the story. It also includes comments made by the writer about the importance of exploring our surroundings, being creative, and seeing ourselves reflected in books. A call to Bishop with her mirrors, windows and sliding doors perhaps? (You can read more about these metaphors here and here).

I really enjoyed reading What I Like Most in a big format. It allowed me to observe the illustrations with attention to details that were not clear to me before (like the watercoloured flowers!). Reading how Murphy’s original idea in the first draft changed through the collaboration with illustrator Zhu-Cheng Liang added depth to the picturebook. The author states that the book can be read both as a listing of enjoyable activities, as a migration story, and even as an example of intergenerational solidarity due to the relation between pictures and text. Her story now has a universal appeal to every person who has had to find refuge in their most liked things, people, and memories to thrive.

With these two exhibitions, the museum has made an impactful statement about the importance of children’s and young adults’ literature in cultural institutions. Childhood and the artefacts created by and for young people should be valued and included in national collections; they should not be seen as second-class, not good enough, not artistic enough, not complex enough. The fact that Nancy Murphy is sharing space with James Joyce is good news about MoLI’s view on young people’s literature and a great general step towards recognising and valuing children’s cultural contributions on an equal footing with adults.

Childhood and the artefacts created by and for young people should be valued and included in national collections; they should not be seen as second-class, not good enough, not artistic enough, not complex enough.

Lastly, a little fun fact. Did you know that Joyce also wrote a children’s short story? In a letter from 1936 addressed to his young grandson, Stephen, Joyce retells a French folktale adding Irish elements to the original narrative. In 1964, it was turned into an illustrated book. You can look it up as The Cat & The Devil. Or, if you happen to be in Dublin, you can enjoy the two exhibitions presented above and go see the book’s first edition with your own eyes.

For updated information about opening times, prices and current exhibitions, please visit the web of the Museum of Literature Ireland.

Leave a comment